July 31, 2017

Trax

on the Trail has helped keep me connected to political events for over a year.

As many of us academics seek ways to respond to the new normal, some of us may

want to do what I did—sign up to participate in blogs like Trax o the Trail.

Most of us agree that now more than ever we need to devote time to the commons

(according to Wikipedia, the commons is the cultural and natural

resources accessible to all members of a society, including natural

materials such as air, water, and a habitable earth. These resources are held

in common, not owned privately). Blogs like Trax are a good way of doing so.

I’m hoping that by sharing my experiences I might help others decide to make

this kind of commitment.

A year ago, Trax on the Trail co-editors James Deaville and Dana

Gorzelany-Mostak asked me to contribute to the blog, partly because of my work

on audiovisual aesthetics and the 2008 presidential election, including

“Audiovisual Change: Viral Media in the Obama Campaign” in my book Unruly

Media: YouTube, Music Video, and the New Digital Cinema.[i]

I was told contributions would be aimed towards a broader public and open to

possibilities. I thought, “Oh great, I’ll just keep one eye on unfolding events

and write on a moment that tugs at me.”

But then not surprisingly I fell into the maelstrom. I became a

track-the-clickbait nail-biter, hoping that with each increasingly outrageous Trump

tweet we would have a reset of the election campaign. I made my way through

vast amounts of corporate-tinged, television-oriented Clinton advertising from

the persuasive to the embarrassing; Trump advertising too, of course. Instances

hailed me, like a “Rickroll”

moment (a phenomenon I’d followed during Obama’s 2008 campaign), or the DNC’s

spoof on Trump’s convention entrance accompanied by Queens’ “We are the

Champions.” It is only now after the January Women’s March that the power of

Elizabeth Banks’ DNC spoof of Trump’s convention entrance feels graspable to

me. The actress’s white crinoline dress and doll-like movements seemed to say

that Stepford wives could possess more authority than Trump.

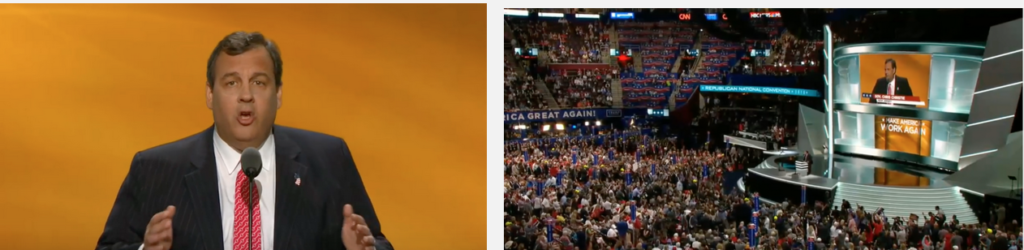

The Republican convention felt like a terrible schematic pulled from scenes of Nicholas Ray’s Johnny Guitar. In Ray’s film, a small-town lynch mob of men, headed by Emma Small (Mercedes McCambridge), a woman overcome with lust/jealousy for Vienna (Joan Crawford), and backed up by streaks of technicolor golds and reds seemed now even more LED-amped up, as Chris Christie and his mob’s increasingly shrill calls and responses of “lock her up” morphed into a twisted cinematic nightmare of the western. Without Trax on the Trail’s light obligation, I’m sure I would have fled from time to time; for me, instead this minimal promise to Trax called on me to connect.

And then, for

better or worse—I overshot Trax, producing work that was the wrong shape or

size. Trump’s provocations could endanger my family and me. I’ve taught in

large red-state schools for many years, and I knew Trump’s simplistic,

authoritarian pronouncements would resonate with many people. There’s also some

residual remorse from when I taught in these places—a sense that somehow I

wasn’t able to sketch a compelling enough counterargument for those with

religious or political views that differed from mine. I’d always assigned some

Karl Marx

and John Rawls, but

these seemed to yield few rewards (a Canadian documentary called The

Corporation, and an Oprah Winfrey infomercial

about working at Google, were more persuasive). Now, in my Stanford bubble, I

know no Trump supporters who might hear my simply-posed argument, like “So you

don’t want the government in your life? But then who and what might take its

place? Corporations? A corporation’s first responsibility is to produce

quarterly reports showing consistently increasing short-term profits for their

shareholders. Upper management’s strongest obligation is to depress wages: a

company may project a thin veneer of care, but in truth labor most often falls

under the same optics as the cheapest available oil or minerals.”

It was in this sudden pressured moment that I was hit by an obvious limitation

we academics have. We have skills at providing historical and cultural context,

we can make persuasive arguments, but most of us don’t write quickly enough,

nor with the kinds of pithy voice valued by popular media like Huffington

Post, Salon,

Slate,

the New

York Times or the Atlantic.

But we can try. If we want to get materials out quickly that might contribute

to the conversation—that are both available to the public and findable in the

academic databases—we need new places to turn.

I’ve posted some

of my contributions to protecting the commons on the Film International Journal

blog “Protecting the Commons.”

The site is open, and I invite readers and other interested publics to post

there as well. I am currently working toward a fleet online journal that might

be responsive to unfolding events, and that might be included in the academic

databases. Materials might be generated at the local level: scholars on

Facebook, Twitter, and blogs might forward their posts to Facebook pages based

on the topic. When work starts to emerge (four or five pieces), they might be

gathered together to be published online.

I still have questions about audiovisual aesthetics and the election, and I’m

hoping I and others will publish about them soon. My basic claim is that

popular music and music video are media we turn to when we need to think about

unfolding events. How might I demonstrate this?

A first basic question: in the era of social media, do we use pop music differently from the way we did in the past? I’ve noticed that on Facebook, music works for me as a quick intensifier, though others may not experience it in this way. I participated in one of the first phone conferences to protect Obamacare. Though the call felt canned (why did they make us listen on a phone at an appointed time to what must surely have been a pre-recorded message?), still I felt I’d made a step toward a contribution with other people’s lives. For the first time after the election, I felt progressives had a chance in the face of a potential new reign of terror (the Women’s March, with the awe-inspiring numbers of 1 of every 100 Americans participating, was still weeks away). For some unplumbed reason, in the evening, I had a yearning for Earth, Wind, and Fire. “Can’t Let Go” resounded through the speakers, and I suddenly felt my toddler, husband, and I would make it through. There just was no way the Trump regime could possibly endure. Later, when I was in the Burbank airport’s long corridors, I heard some more Earth, Wind, and Fire, and I thought the person who programmed the music must have been feeling like me (Dana Gorzelany-Mostak has noted, EWF’s precision chimes with Obama’s, an attention to detail, equipoise, uplift, and grace).

Similarly, I was anguished during the electoral college vote, and perplexed by what friends were posting on Facebook. I noticed a satirical audiovisual clip about Trump loving Putin at the top of my Facebook feed. I was suddenly newly poised to disseminate, analyze, and promote. Are my visceral responses a function of our highly saturated media environment?

And how much can an ad or a gif or a music video mobilize a community? Which pieces mattered in this election? How much do music and music videos mirror our moment, and can they serve as a lens to help us understand where we came from and where we might be going? (This is an argument Siegfried Kracauer made in his book Caligari’s Children: The Film As Tale Of Terror. For Kracauer, fascism was nascent but also self-evident in Weimar-period popular culture.) I noticed that the Chainsmokers mirrored Trump’s aesthetics, though without realizing it (during concerts they stopped songs and admonished crowds not to vote for Trump). The Chainsmokers’ videos tout white male privilege, asserting both their cultural powerlessness and their dominion over women (and thereby claiming the right to seize women’s bodies). Their music is painfully white. Their live shows and videos were the hit of this past summer. I wonder if we might have seen it coming. Of course, the people who spoof are on it. There’s a mash-up of Trump singing “Closer,” but I prefer the mash-up of him singing emo.

Post-election, many

music videos are muddy and dark (sharing a palate with Pepe

the Frog), as if the musicians and the directors are trying to modulate

their sense of depression. I can’t believe music videos would look this way had

Clinton been elected. Trolling still remains an issue. (Note the ways Shia

Lebeouf has been chased by trolls and Pepe the Frog simply for a radio podcast

and a white flag.) I don’t know all of the ways the entertainment industry is

coping.

Sadly, many blogs now seem to be going into hiatus or shutting down just when

we need them the most. Some people call this “Trump Burnout,” authors and

readers needing to carry on in the face of what feels like shrinking

possibilities. Trax may take a hiatus, and Antenna closed up shop. I hope new

forms will emerge to combat our new normal. The future, of course, is

uncertain—many of the newest technologies, from psychometrics, big data, to

A.I, seem double-edged. We’re waiting for a new contingent to help us face

what, for right now, feels like an ever-darkening horizon.

– Carol Vernallis

[i] Carol Vernallis, Unruly Media: YouTube, Music Video, and the New Digital Cinema (New York: Oxford, 2014).