July 21, 2016

The stage is set for a political event. American flags are strewn about a platform set with two podiums, and an audience sits, rapt with anticipation, waving signs supporting the candidate. A gentleman in a clean-cut suit steps up to one podium, but instead of delivering a stump speech, he begins rapping: “How does a bastard, racist/son of a millionaire and a mogul/dropped in the middle of a race of the Republicans in tatters/a party nearly shattered/somehow become the only one that mattered?”

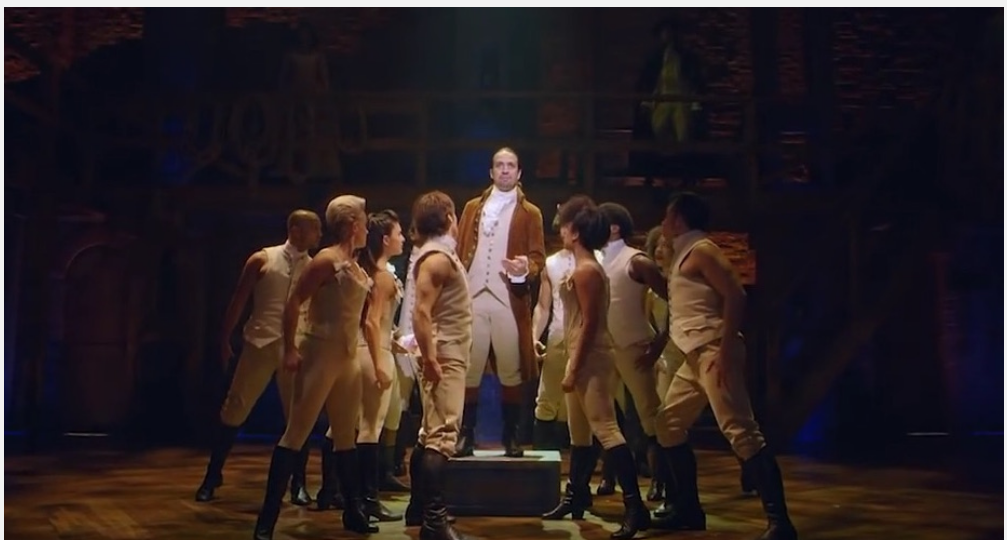

This unlikely scene is the beginning of HamilTrump, a sketch by the New York-based Rad Motel that parodies the opening number of Lin Manuel-Miranda’s Hamilton (2015), a Broadway musical that tells the story of the titular founding father. Like most comedies, the laugh in this scene comes from the disconnect between expectations and realization. Flags and podiums usually imply serious discussions and real policy platforms, not rapping and insults. The presence of Hamilton also contributes to the comedic atmosphere, as any audience familiar with the original not only hears the actor reciting the lyrics, but holds those lyrics up against Miranda’s original opening to Hamilton: “How does a bastard orphan/son of a whore and a Scotsman/dropped in the middle of a forgotten spot in the Caribbean/by providence, impoverished, in squalor/grow up to be a hero and scholar?” The “racist” “billionaire” Trump, Rad Motel implies, is the opposite of the scruffy but brilliant Hamilton.

This comic reversal is at the heart of the satirical act of parody, an art that relies on doubleness: the audience places the two texts (the original and its parody) side-by-side in their minds, with the comedy resulting from the ironic distance between the two performances, as in the case of HamilTrump original and its parody (Hutcheon, 31). Parody has a long history in electoral politics, and Rad Motel is not the only group who has found Hamilton a useful tool in 2016; a self-described “bunch of millennials who have too much free time on their hands” crowd-sourced a Google Document of an entirely new libretto for the show called Jeb! An American Disappointment, based on the Bush campaign.[i] Comedians have also turned to other musicals to comment on the presidential election: Jimmy Kimmel reunited Nathan Lane and Matthew Broderick of 2001’s The Producers for a segment on his late night show. The original musical tells the story of two crooked showmen who raise a million bucks by promising all investors a 50% stake in the show, put on a $100,000 flop, and try to run off with the extra money, but the plan fails when their show becomes a hit. In Kimmel’s version, Trumped, two political consultants raise money for a terrible presidential candidate and plan to keep the extra cash when the candidate inevitably drops out. The candidate, of course, is Trump, and the consultants are left in the same lurch when his campaign unexpectedly takes off.

Musicals in general make for good political parody because they also rely on a kind of doubleness, in which the story is both depicted in the action and retold through the songs. This doubled narrative allows characters to explain their thoughts and their processes to the audience, to “tell” rather than “show,” even if the characters onstage don’t necessarily need that explanation. This kind of “process” number exists as “The Ten Duel Commandments” in Hamilton, which becomes “The Ten Debate Commandments” in Jeb!. In both musicals and their parodies, this allows the author to highlight the ridiculousness of the character’s actions; what seems to be a logical sequence of events if looked at one by one appears utterly ludicrous when taken as a whole. It is no coincidence that the number from The Producers that features most prominently in Trumped is the beginning of “We Can Do It,” in which the step-by-step plan for defrauding investors is transformed into a step-by-step plan for defrauding campaign donors. Although in the parody version Lane and Broderick don’t sing, anyone familiar with the original show would hear those flourishes in the background, adding an extra touch of silliness to the proceedings. This strategy of telling rather than showing packs a lot of information in a very short amount of time, which is essential to comedy. Brevity is, after all, the soul of wit.

Furthermore, this doubled narrative structure allows characters to sing their subtext (Clum, 310). In other words, what characters sing is understood to be their true feelings, even if their actions outside the song contradict their lyrics. This works well with the idea of parody, which often makes the subtext of the original into the text of new version. (Trevor Noah’s monologues “translating” network news on the The Daily Show, making hidden biases explicit, is a good non-musical example). In musicals, that which is sung is understood to be the characters “true” feelings. This idea works well with the electoral parody, which appears to reveal a candidate’s true intentions (or at least what the author of the parody believes those intentions to be) beneath the political doublespeak. For example, in HamilTrump, the chorus comically explains the candidate’s strategy to win the Presidency: “Scamming for every vote he can get his hands on/planning for the White House see him now as he stands/at the Capitol building with a bible in hand/make America great again without a real plan.”

To return to the idea of ironic distance in parody, this works on the level of the larger concept of the musical itself. Both historical musicals like Hamilton and backstage musicals like The Producers are often retellings of the Cinderella story: the chorus girl made good in 42nd Street (1933) or Evita (1978), the unknown immigrant’s rise to power (Hamilton), or even a contentious group of colonists becoming a nation in 1776 (1969). When a form that usually glorifies the “pull-yourself-up-by-your-bootstraps” story is applied to the lives of Trump and Bush—two very rich men—hilarity ensues. It also helps to explain why the Above Average sketch “Hillary Clinton Ruins Hamilton” works. Although Above Average does not employ the same double narrative structure of the direct parodies of Hamilton, the group plays on the idea that Hillary Clinton—another very wealthy individual—is out of touch with the population that she wants to reach and that Hamilton claims to represent: those struggling to make good on the American dream.

This disjunction between form and content also comments on what types of people our culture now considers heroes. Each of the backstage and historical musicals listed above reimagines the “American Dream” to suit contemporary audiences, whether emphasizing New Deal-era cooperation in 42nd Street (Roth, 45), the class and the racial politics of the 1960s in 1776 (Harbert, 142–145, 155–162), or the melting-pot sensibility of the 21st century in Hamilton. Putting the wealthy Bush or Trump at the center of such a show points out the irony of what kinds of people our contemporary culture makes into heroes. Indeed, in Hamilton, the title character declares that “Just like [my] country/I’m young, scrappy and hungry,” emphasizing the classic vision of the American Dream. But the nation, as embodied in the milquetoast Bush of Jeb! is not “young, scrappy, and hungry,” just “excitable and jumpy,” ready to latch on to the next celebrity who comes along, no matter how unworthy.

The ironic distance in Trumped works slightly differently. Kimmel’s version of The Producers draws similarities between the devious scheme at the heart of the original show and what Kimmel sees as the disingenuous nature of Trump’s campaign. We all hope that the electoral process is populated by serious people who genuinely want to serve the nation, but Trumped portrays the political world as nothing more than theatre, a medium that depends on people pretending to be something they are not. The ironic distance isn’t between the parody and the parodied, but between the performance and how we hope the world works.

The musical styles of Hamilton and The Producers also reinforce the ironic distance. Hamilton’s innovative score mixes hip-hop, R&B, and jazz with more traditional Broadway styles. All of these styles, but particularly hip-hop, tend to be associated with the under-privileged—for example, “The Message” by Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five, which is referenced in Hamilton, or, the under-privileged made good (“Still D.R.E.” by Dr. Dre Featuring Snoop Dogg), which further emphasizes the distance between form and content. The aforementioned “The Ten Debate Commandments” is a good example of how this works on the musical level. The original song from Hamilton is based on The Notorious B.I.G.’s “The Ten Crack Commandments” (Miranda and McCarter, 95). Both Miranda’s and B.I.G.’s versions describe the rules of a dubious but sometimes glamorous illegal activity with a laid-back, confident delivery over the slow “boom-bap” beat that is associated with classic “Gangsta” hip-hop, all musical signifiers of coolness, power, and control. In Jeb! this throws into sharp relief the fictional Bush’s timidity in the debates. If Hamilton and Biggie are “Gangstas” in both the good and bad sense of the word, Bush is most certainly the opposite.

In Trumped, the closing number of the sketch (newly composed for Kimmel) also draws on musical style to make its point. The over-the-top Broadway-isms of the song—its rapid strings of internal rhymes, syncopated horn parts, and shimmering hi-hat-based percussion—combine with the showgirls and jazz hands to emphasize the theatrical qualities of Trump’s candidacy. Since theatricality is often seen as being at odds with sincerity, the musical style reinforces Rad Motel’s message that Trump is a phony candidate who entered the race for money and attention.

But, with apologies to Kimmel, electoral politics are often as much about theatre as they are about policy, as candidates try to grab the attention of the electorate in order to spread their message. The fact that we’ve seen an increase in the use of Broadway musicals both by candidates and the electorate speaks to the heightened theatricality of this particular election cycle. The most theatrical of these candidates is definitely Trump, and now that he has clinched the Republican nomination, history certainly has its eyes on him. Maybe in 200 years, we’ll see a full musical about his candidacy.

– Naomi Graber

[i] A useful comparison to HamilTrump is actress and producer Tabitha Holbert’s Sanders, which rewrites the same number to be about the political career of the eponymous Democratic candidate. But unlike HamilTrump, Holbert uses the musical to sketch the similarities between Bernie Sanders and Alexander Hamilton; according to Holbert, both Sanders and Hamilton share an unkempt and brusque style. For more 2016 Hamilton parodies, see “Donald Trump” (created by Tyler Davis) and “Ted Cruz, Loser” (created by 2KSlam Show).