July 7, 2016

In fall of 2015, Trax on the Trail joined forces with Prof. Emily Abrams Ansari’s Music and Politics class at Western University in Ontario. Each student penned an essay or created a podcast that explored a specific intersection between music and presidential politics.

In January, Nikki Pasqualini offered her insight on the 2004 Vote for Change Tour, in March, Caroline Gleason-Mercier addressed the musical activity surrounding William Henry Harrison’s 1840 campaign, and in May, Gary Jackson investigated Saddam Hussein’s use of the ballad “I Will Always Love You” during Iraq’s 2002 referendum.

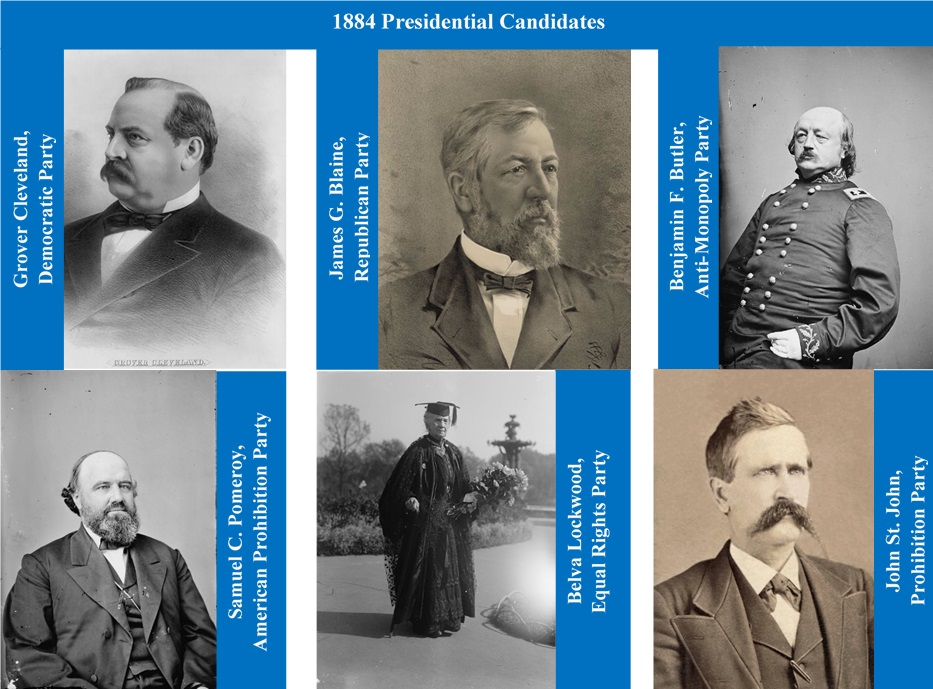

Today we rewind the campaign clock once again to bring you Rebecca Shaw’s essay on the music strategy of Belva Lockwood, a presidential contender who began chipping away at the glass ceiling a century before Hillary Clinton came onto the political scene. Lockwood (much like Clinton), entered the stage to a “Fight Song”…and we can thank none other than George Frideric Handel for that!

***

Why not nominate women

for important places? Is not Victoria Empress of India? Have we not among our

country-women persons of as much talent and ability? Is not history full of

precedents of woman rulers?

—Belva Lockwood, 10 August 1884

The year was 1884. National female suffrage in the United States was still thirty-six years away from fruition, and although women had been involved in electoral campaigns since the 1840s, they had yet to see their names on the ballot. Then, Belva Ann Lockwood ran for president.

The first woman to practice law in the Supreme Court and a staunch supporter of women’s rights since the 1860s, Lockwood was not delusional about her chances. Her aim was not the presidential seat; rather, by running for presidential office, she hoped to bring a fundamental constitutional issue to the forefront of national debate. As she stated in her first campaign speech in Maryland, “I cannot vote, but I can be voted for.”

Lockwood’s campaign for social and political change required a delicate balancing act. Because the American government was controlled by white, male voters, a woman’s identity inevitably clashed with her national identity, which was politically defined by its male electorate. However, Lockwood’s political aspirations required her to reconcile these too seemingly opposing identities; if she were too female-centric, she would lose any hope of gaining male support—the only means by which to achieve political reform. Thus, Lockwood presented female suffrage as an inherent part of America’s political establishment, not a radical overhaul of its socio-political structure: She states, “The word ‘man,’ which occurs in the constitution, has always, when properly defined, been construed as a general term, including woman.”[i] Her campaign was not an attack against the white, American, male self; it was a recognition and fulfillment of a person’s constitutional rights, regardless of gender.

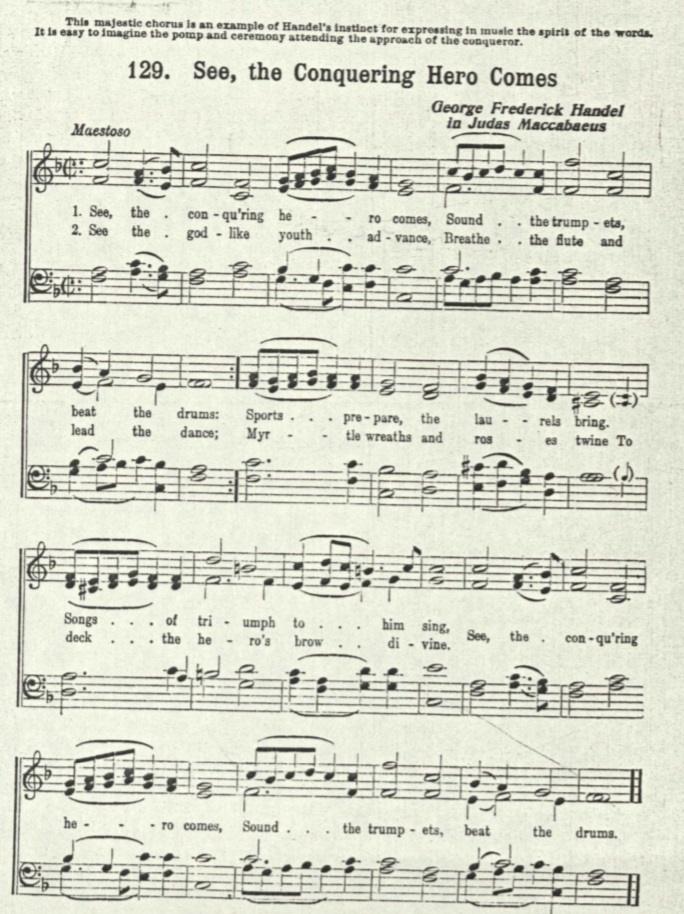

At a rally in Louisville, Kentucky, Lockwood’s use of “See the Conquering Hero” from Judas Maccabaeus by George Frederick Handel (1746) was central to the construction of her female-national identity. It simultaneously drew attention to women’s rights, combatted gender stereotypes, and reduced the radical perception of her campaign. Through the chorus’s musical language, text, and external associations, she created a world—even if it was only temporary—where female and national identities were mutually compatible, not polar opposites.

As Lockwood was a female third-party candidate who entered the playing field two months before the election, the initial public response to her bid for presidency was one of incredulity. The perceived absurdity of her campaign is evident in a 4 October newspaper report from Louisville entitled “Running Against Belva Lockwood: Joe Mulhatton Nominated for President by the Drummers.”[ii] Through his reference to Mulhatton—a famous hoaxer in America during the 1870s and 1880s—the reporter cast doubt on Lockwood’s validity as a presidential candidate.

Less than two weeks after the Mulhatton comparison, Lockwood arrived in Louisville, where she used music to help establish the sincerity of her campaign. By employing an eighteenth-century oratorio chorus rather than a more recent, popular song, Lockwood aligned herself with an established tradition instead of a passing fad. Furthermore, the chorus’s musical language was tonal and simplistic, the melody repetitive and memorable. As such, its longevity and aural simplicity served to lessen the radical appearance of her campaign; if the music was not rebellious, why should her campaign be any different?

The broad basis of her campaign and the mellowing of certain feminist issues (e.g., she removed her initial promise of equal delegation of political offices among genders and minorities) likewise created the image of a serious campaign that catered to both female and male supporters. Rather than forcing women’s rights down the throats of the nation, her speeches addressed issues that were amenable to a general populace. For instance, in Louisville she focused on the economic future of America—not female suffrage—criticizing both the Democratic support of free trade and the Republican’s endorsement of high tariffs. Her campaign sought to gain support for female suffrage by demonstrating a woman’s proficiency as a leader and politician. If America could see a woman completing the tasks of the most prestigious male job in the country, perhaps they would allow women to step outside of the kitchen.

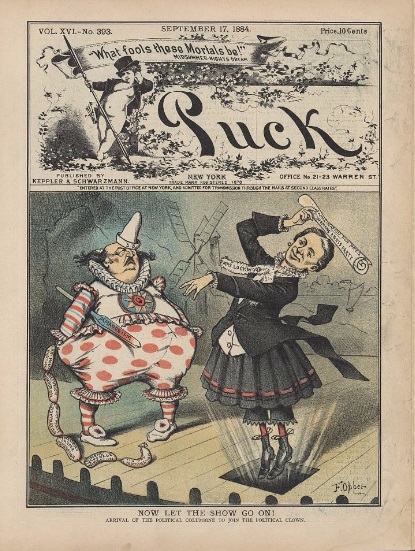

Because newspaper reports of Lockwood’s campaign—both positive and negative—defined her primarily by her gender, rather than her political views, it was difficult for Lockwood to portray herself as the potential leader of a country. The stereotypical whimsical perception of women negated the leadership qualities required of a presidential candidate. For example, articles commonly highlighted her clothing at the beginning of an article and relegated the analysis of her political views to a few sentences at the end: “Mrs. Lockwood was attired in black silk throughout, a pair of black-rimmed eye-glasses rode upon her Grecian nose, and her dark eyes sparkled behind them. . . .”[iii] The same article noted that her supporters were mostly “middle aged virgins.”[iv] Another article stated, “Belva is no exception to other women, and women as a rule are not reasonable. They are governed by their impulses, and impulses are not safe guides in the matter of appointments to office.”[v] Caricatures, such as this one from Puck, likewise emphasized the stereotypical emotional concerns of women.[vi]

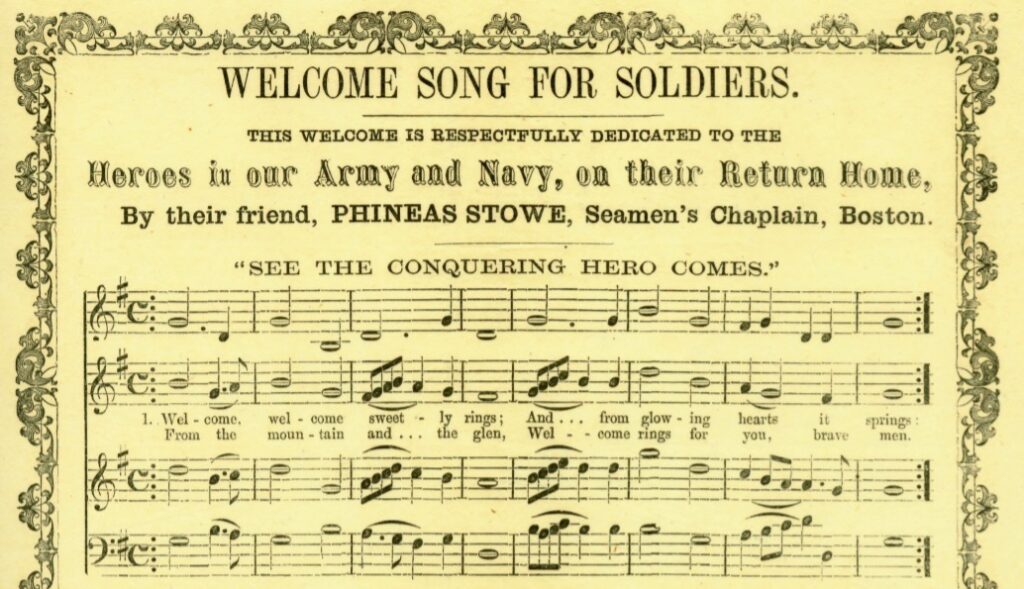

The militaristic and heroic nature of “See the Conquering Hero Comes” combatted gendered stereotypes by signifying an idealized male military hero on three levels: (1) the oratorio was written to commemorate the Duke of Cumberland’s victory at the Battle of Culloden (16 April 1746); (2) the oratorio’s storyline celebrates the heroism of its title character; and (3) various arrangements of the chorus were commonly used by military marching bands. For instance, the Boston chaplain, Phineas Stowe, used the music to set his own text, “Welcome Song for Soldiers” (1865), to hail the “Heroes in our Army and Navy, on Their Return Home.” Even in its original instrumentation, the chorus’s use of brass instruments and its quadruple meter are strongly reminiscent of a military march. By implementing this chorus in Louisiana as she stepped off of the train, Lockwood situated herself as the “conquering hero.” Under the guise of a male hero of war, she could be perceived as an appropriate candidate to run for the leadership of America, a perception that was seemingly incompatible with nineteenth-century female stereotypes.

Judas Maccabaeus’s account of Jewish persecution and heroism could be compared to the discrimination against women and the subsequent retaliation of female suffragists. Mary Wollstonecraft, a well-known British suffragist, quoted a portion of the oratorio in her novel, Maria (1798), when the titular character escapes from her abusive husband: “Come, ever-smiling liberty, / And with thee bring thy jocund train.”[vii] Here, there is an interesting parallel to Lockwood’s campaign: in her political platform, she promised—among other things—to reform family law so that “the wife [would be] equal with the husband in authority and right, and an equal partner in the common business.”[viii] In Wollstonecraft’s novel, Maria turned to Handel’s oratorio when she defied the sanctimony of marriage and fled her abusive husband; Lockwood invokes this composition in her campaign to imply that such an act would be legally supported should she be elected. Furthermore, although Lockwood’s brass band arrangement was instrumental, those who knew the chorus would have also realized that, in its original setting, it would be performed primarily by women; male and female voices do not unite until the third section, after the Chorus of Youths (often sung by women) and the Chorus of Virgins. In this chorus, women play a primary, not secondary, role.

The chorus’s clearly articulated connection to the military and male heroic stereotypes reflects the challenges that Lockwood faced in her campaign. Her support of women’s rights was obvious, but her leadership qualities were less apparent to the general public, due to the gendered newspaper coverage and prevalent gender stereotypes of the time. As such, the chorus serving as her campaign soundtrack emphasizes her “masculine” virtues as much as possible.

Although Lockwood ultimately lost the election, receiving only 4149 votes, her contribution to female suffrage in America deserves remembrance and celebration. Her political campaign—amplified by her musical selection—demonstrated to America that women were essential to its national identity and fully capable of sitting in the White House—let alone voting in elections. Nonetheless, Lockwood did not live to see national female suffrage become a reality. The nineteenth amendment to the Constitution was passed in 1920, three years after her death.

To this day, Belva Lockwood remains the only woman to carry out a full campaign for American presidency; one can only hope that someday her dreams become a reality. As she stated at the age of 84:

I look to see women in the United States senate and the house of representatives. If [a woman] demonstrates that she is fitted to be president she will some day occupy the White House. It will be entirely on her own merits, however. No movement can place her there simply because she is a woman. It will come if she proves herself mentally fit for the position.[ix]

– Rebecca Shaw

[i] Belva A Lockwood, “The Consent of the Governed,” The Woman’s Journal, Iss. 41 (Boston, MA, United States) October 11, 1884, p. 327. http://tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/meVz7.

[ii] “Running Against Belva Lockwood: Joe Mulhatton Nominated for President by the Drummers, Chicago Daily Tribune, October 4, 1884, p. 3.

[iii] “A Woman Can Be President: Mrs. Lockwood Defines the Position of the Equal Righters,” New York Times, October 20, 1884, p. 5.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] “Belva’s Letter,” Chicago Daily Tribune, September 6, 1884, p. 4.

[vi] Frederic Burr Opper, “Now Let the Show Go On!” Puck 16, no. 393 (New York: Keppler & Schwarzmann, September 17, 1884), cover, http://www.loc.gov/item/2011661827/.

[vii] Mary Wollstonecraft, Mary, A Fiction and The Wrongs of Woman, or Maria, ed. Michelle Faubert (Peterborough: Broadview Press, 2012), 262.

[viii] “Belva Lockwood’s Hopes: The Female Candidate for the Presidency of the United States,” Atlanta Constitution, September 5, 1884, p. 1.

[ix] “Belva Hippodroming: The Equal Rights Candidate Outlines Her Policy in the Opera House at Cleveland,” Boston Daily Globe, October 13, 1884.