In unsettled times like our own, it is tempting to assume that the confluence of events is unprecedented: 2020 has already brought us an impeachment trial, a global pandemic, a sudden shift from prosperity to recession, a worldwide protest movement against racial injustice and police brutality, and a presidential primary unlike any other. But the period from 1917 to 1920 featured an eerily similar confluence of events: a world war, a global pandemic, an increase in racial and ethnic injustice, a president whose incapacitation by stroke was hidden from the public, and constitutional amendments instituting prohibition and women’s suffrage. The events preceding the 1920 election were different from those preceding the 2020 election, but they parallel closely the confluence of social and historical changes, as reflected in the musical compositions and concert life of the era.

When the “European War” began in the summer of 1914, US public opinion was divided. The strong pacifist and isolationist sentiments in the country were bolstered by the popular song “I Didn’t Raise my Boy to be a Soldier,” written in 1914 by Alfred Bryan and Al Piantadosi. It was recorded by multiple singers and became the country’s most popular song early in 1915. The Victor recording by Morton Harvey is characteristic:

Taking the opposite view was former Pres. Theodore Roosevelt, who advocated for military preparedness and support of the Allies while also chastising “hyphenated Americans,” who claimed loyalty to the United States but also retained attachments to their ethnic heritage. His speech delivered on Columbus Day 1915 in New York became a rallying cry for those who pursued restrictions on German-Americans, their language, and their culture.[1]

Pres. Woodrow Wilson walked a fine line in his re-election campaign of 1916, when he touted his accomplishments with the slogan “He kept us out of the war.” Within months of his election, however, the war came closer to home, and by April, public opinion had turned decisively, and Congress declared war on Friday, April 6. Popular songwriter George M. Cohan was so moved that he wrote the well-known song “Over There” on Saturday, April 7.[2] Introduced by vaudeville star Nora Bayes in June, it became an instant hit that encapsulated the national mood of enthusiastic support for the beleaguered Allies across the ocean.

Performed by Nora Bayes

As I have described in my recent book on this era, 1917 saw a seachange in American attitudes toward music and musicians.[3] Many German musicians who had previously held positions of leadership in classical music were publicly criticized or removed from their positions. Even well-connected German-American musicians like New York Symphony conductor Walter Damrosch were forced to defend themselves vigorously and alter their programming to eliminate contemporary German and Austrian works. “The Star-Spangled Banner” became a litmus test that could be used to stir crowds to patriotic fervor or cast suspicion on those who neglected to feature it. The Metropolitan Opera eliminated all German repertoire, and Karl Muck, the conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, was widely criticized and eventually interned after he neglected to play the anthem before a concert in Providence, RI (Fig. 1).[4]

Amid the turmoil of the war, the world was beset by a virulent strain of influenza that killed more than fifty million people. The first wave of the flu in winter 1918 seems to have begun in Kansas and spread primarily through military encampments. When it returned in a much more lethal mutation in the fall, Wilson’s administration chose to ignore the pandemic so as not to distract the nation from the war effort. Without timely warnings or public health directives, military transports and Liberty Bond rallies became breeding grounds for the virus, leading to an estimated 675,000 deaths in the United States. In 1918 as in 2020, Federal officials chose to delegate public health measures primarily to state and local officials, leading to an uncoordinated response.[5]

The peak of infections in October 1918 coincided with the anticipated opening of the classical music season, forcing many organizations to delay the start of concerts because of local shutdown restrictions.[6] Concert tours were postponed, major symphonies delayed their season openings for weeks, and performers hunkered down to avoid contracting the illness. In the absence of video streaming, television, or even broadcast radio, however, music-hungry audience members were much more eager to reinstate live concerts. Among the significant musicians who died in the 1918–1919 pandemic were the eminent British composer Sir Hubert Parry, the vaudeville impresario A. Paul Keith, the concert singer Sada Doak, and Henry Ragas, pianist of the Original Dixieland Jazz Band. Tin Pan Alley composers produced several songs on the theme of influenza, but few were as graphic and emotional as the apocalyptic protest song “The 1919 Influenza Blues.” The message of the song—that a pandemic attacks rich and poor indiscriminately—has potent echoes in 2020. The song circulated among blues singers for decades and is heard here in a 2004 recording by Essie Jenkins:

Performed by Essie Jenkins

Late in the pandemic, the flu virus infected its most influential victim when Woodrow Wilson contracted it in France at the height of negotiations of the Versailles Treaty. Although impossible to prove, it is likely that Wilson’s illness—which affected his mental state and his stamina—contributed to his inability to broker a compromise to the harsh terms demanded by the French and the eventual failure of his beloved League of Nations.[7] Four months after his bout with the flu, Wilson suffered a debilitating stroke, the culmination of over twenty years of cerebrovascular disorders. His wife and personal physician led a cover-up to avoid alarming the president or the nation. Publicly he did not disavow his intention to run for a third term, but privately his Cabinet was concerned about his ability to fulfill his duties in 1920. His party’s indecision delayed the choice of a replacement presidential candidate, allowing for the landslide election of Warren G. Harding, who is generally ranked among history’s worst presidents.[8] Harding ran a “front porch campaign” with minimal traveling, and his undistinguished but catchy campaign song was written by vaudeville star Al Jolson[9]:

Performed by Oscar Brand (Smithsonian Folkways Recordings)

Harding ran on the slogan “Return to Normalcy,” but America had been changed irrevocably by the previous decade. The 1919 hit “How Ya Gonna Keep ‘em Down on the Farm (After They’ve Seen Paree)?” was about much more than farm labor shortages. The song encapsulated American attitudes toward youth, internationalism, music, and the growing urban/rural divide. This recording was made by Lt. James Reese Europe’s “Harlem Hellfighters” Band in 1919, with vocals by Noble Sissle. The musicians were part of the 369th Infantry, one of the most decorated African American units of the US Army.

Performed by Lt. James Reese Europe’s “Harlem Hellfighters” Band

In his speeches and writings, Harding advocated equality for African Americans and supported a Federal anti-lynching bill, but he was unable to obtain passage of meaningful legislation. The war had brought admiration for the hundreds of thousands of African American soldiers who fought bravely in France, but the post-war years saw a resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan, the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921, and widespread efforts at Black voter suppression. Paradoxically, the 1920s saw a flourishing of music and literature by African Americans at the same time as widespread discrimination.[10]

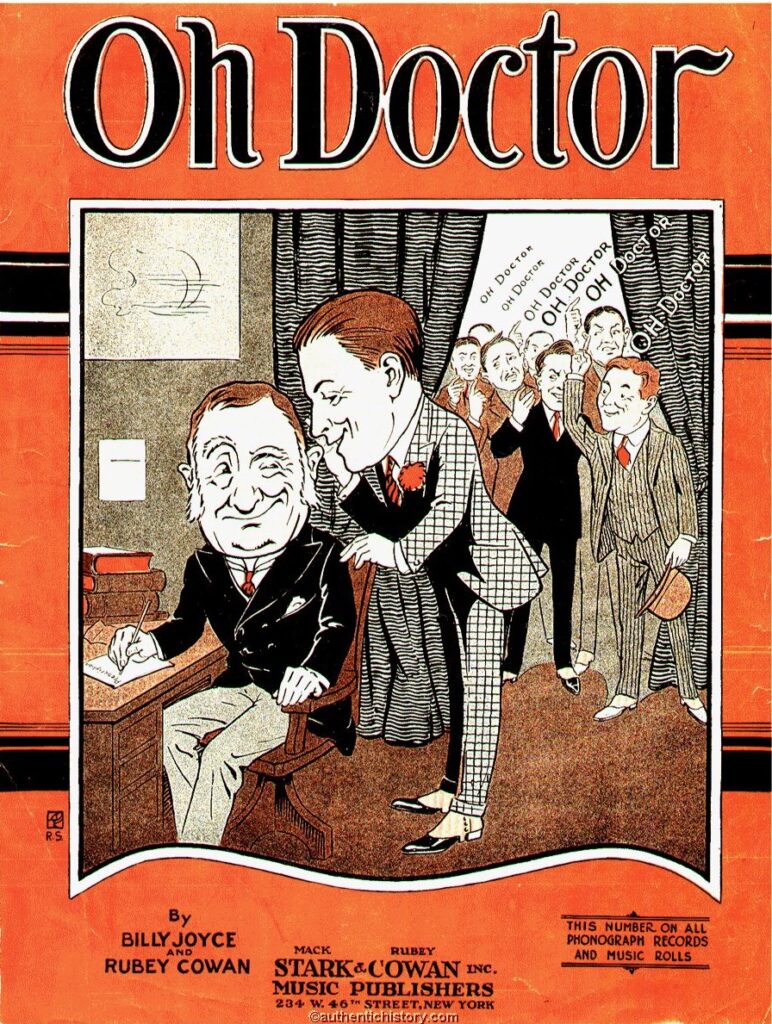

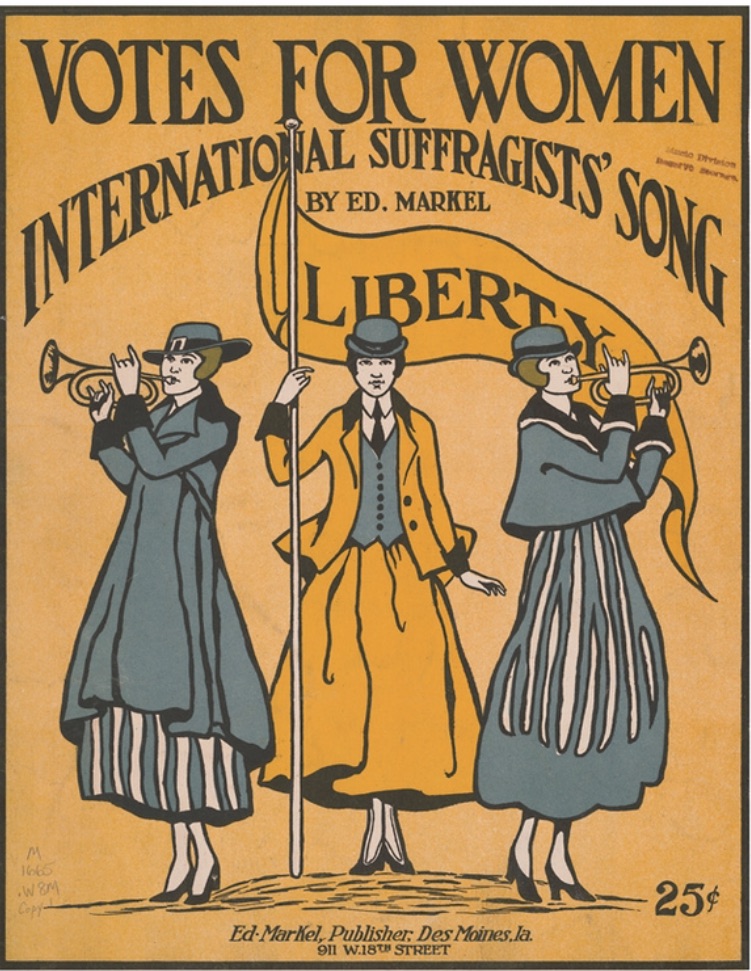

The failure of legislation addressing racial injustice was contrasted by the passage of two Constitutional amendments with far-reaching impacts on American society. The 18th Amendment, ratified on January 16, 1919, prohibited the manufacture and sale of alcohol in the United States. This law was the culmination of decades of Prohibitionist activism against widespread alcohol abuse, but opponents argued that its draconian measures created more problems than it solved. Songwriters had a heyday with a culture that was suddenly forced to go “dry” (Fig. 2a).[11] The 19th Amendment, ratified on August 18, 1920, granted women the right to vote. Although suffragists had worked for decades at great personal sacrifice to achieve this goal, women’s suffrage was not in the end controversial and quickly came to be accepted as the new norm in the US and other countries. A digital collecton of sheet music covers from the Library of Congress documents the musical aspects of the suffrage movement with over 200 examples from 1838 to 1923 (Fig. 2b).[12]

The historical message of this era is that the confluence of multiple important events can be as tumultuous as the events themselves. Then as now, times of change on multiple fronts inspire disagreement on which change is most important. For Woodrow Wilson, the war was so consuming that he refused to take decisive action on the influenza pandemic, thereby increasing the death toll through inaction. Austrian-American opera star Ernestine Schumann-Heink was so committed to pacifism that she urged suffragists to abandon their campaign for the vote in order to promote neutrality, evidently believing that activists could concentrate on only one issue at a time.[13] Most tragically, African Americans who had earned respect for their role in the war quickly saw their status undermined by reactionary nationalism and a resurgence of racism, contributing to the Great Migration of Blacks to northern cities.[14] The confluence of events in the late 1910s offers a potent precursor to the confluence of momentous changes sweeping the US in 2020 and a timely reminder of the importance of doing more than one thing at a time.

– E. Douglas Bomberger

[1] “Roosevelt Bars the Hyphenated: No Room in this Country for Dual Nationality, He Tells Knights of Columbus,” New York Times, October 13, 1915, p. 1.

[2] For a picturesque description of the song’s composition and its effect on his daughter Mary, see Glenn Watkins, Proof Through the Night: Music and the Great War (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003), 257–59.

[3] E. Douglas Bomberger, Making Music American: 1917 and the Transformation of Culture (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).

[4] See Melissa D. Burrage, The Karl Muck Scandal: Classical Music and Xenophobia in World War I America (Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, 2019); and E. Douglas Bomberger, “Taking the German Muse out of Music: The Chronicle and US Musical Opinion in World War I,” Journal of the Society for American Music 14, no. 2 (Spring 2020): 141–75.

[5] For a thorough discussion, see John M. Barry, The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History (New York: Viking Penguin, 2004).

[6] William Robin, “The 1918 Flu’s Impact on Music? Not Major,” New York Times, May 7, 2020, p. C3.

[7] Barry, Great Influenza, 382–88, and Steve Coll, “Woodrow Wilson’s Case of the Flu and how Pandemics Change History,” The New Yorker, April 17, 2020, https://www.newyorker.com/news/daily-comment/woodrow-wilsons-case-of-the-flu-and-how-pandemics-change-history.

[8] University of Arizona Health Sciences Library, “Woodrow Wilson: Strokes and Denial,” https://ahsl.arizona.edu/about/exhibits/presidents/wilson, accessed June 29, 2020.

[9] Maury Thompson, “Al Jolson and Harding’s ‘Front Porch Campaign,’” New York Almanack, July 20, 2020 https://www.newyorkalmanack.com/2020/07/al-jolson-and-hardings-front-porch-campaign/.

[10] For a selection of resources from the voluminous scholarly literature on the Harlem Renaissance, see the Fordham University library guide to the topic: https://fordham.libguides.com/c.php?g=279554&p=1863153 as well as the Library of Congress digital research guide: https://guides.loc.gov/harlem-renaissance.

[11] Ken Burns and Lynn Novick explore the issues and images of the era in their documentary Prohibition, https://www.pbs.org/kenburns/prohibition/. Examples of sheet music addressing prohibition may be found at “Music About the Prohibition Era,” https://www.historyonthenet.com/authentichistory/1921-1929/2-socialchange/1-prohibition/2-music/.

[12] Library of Congress exhibition, “Women’s Suffrage in Sheet Music,” https://www.loc.gov/collections/womens-suffrage-sheet-music/about-this-collection/.

[13] “Ask Women to Stop War: ‘I’d Die to End it,’ Says Schumann-Heink,” Davenport Daily Times, January 4, 1915, p. 10.

[14] For a discussion of the Great Migration as a reaction to the Jim Crow Era, see Isabel Wilkerson, The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration (New York: Vintage, 2010).