September 13, 2016

In the context of political campaigns, music is almost always linked to a visual context, be it a campaign rally or political spot.[i] The interaction of audio and visual elements is central to understanding such political communication. This was driven home to me during the second session of the Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia in late July. Host Elizabeth Banks produced a music video featuring “her friends” (a variety of celebrities including actors and musicians) performing an a cappella version of Rachel Platten’s “Fight Song.” The song had been played at the end of Hillary Clinton’s campaign events around the country for months.[ii]

As a rally anthem, the song at some level seemed mismatched.[iii] Clinton is nearly twice as old as Platten, whose pop music peers are artists like Katy Perry, Taylor Swift, and Kelly Clarkson. As such, the song comes across as a somewhat craven attempt to appeal to younger voters or to make the candidate appear more current. Many commentators saw the release of Mrs. Clinton’s first Spotify playlist in June 2015 in exactly this light.[iv] As Daniella Diaz noted on CNN’s website, “None of the 14 songs on the 67-year-old candidate’s playlist was released before 1999 ….” (Diaz 2015). On the website RealClearPolitics.com, Courtney Such wrote: “The second-oldest presidential candidate (third-oldest if Joe Biden gets in) is no fuddy-duddy: she now has a campaign playlist” (Such 2015). And in an article on the Guardian website titled “Just One of the Cool Kids,” Jana Kasperkevic described the playlist as “mostly geared towards the millennial female voter” (Kasperkevic 2015). Given Mrs. Clinton’s well-documented struggles with authenticity and trust, this can perhaps be seen as at least awkward if not problematic.[v]

Ms. Banks herself embodies a complex constellation of attributes that might evoke various associations in the minds of viewers. There are the roles that she has played in films. She is, of course, widely known for playing Effie Trinket, an ultimately sympathetic rebel who evolved out of a shallow striver working as a “handler” for contestants in The Hunger Games films. There is her present status as a rare rising female power in Hollywood production; such status, it should be noted, ranks differently for Democrats and Republicans.

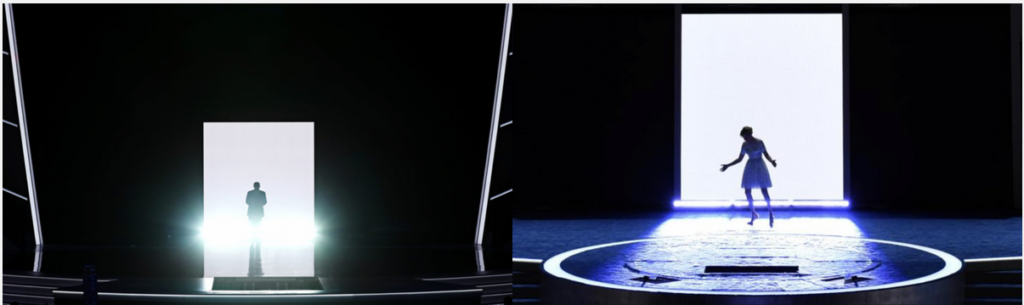

Perhaps it is the power of the Effie Trinket association that led to Banks taking the stage in Philadelphia in an over-the-top, backlit parody of Donald Trump’s entrance when he introduced his wife at the Republican National Convention a week earlier in Cleveland (Fig. 1a & ab). Banks underscored the point in her DNC remarks: “Some of you know me from The Hunger Games, in which I play Effie Trinket, a cruel, out-of-touch reality TV star who wears insane wigs while delivering long-winded speeches to a violent dystopia. So when I tuned into Cleveland last week, I was like, ‘Uh, hey! That’s my act!’”[vi]

While Banks has played numerous comic and romantic roles in films such as Wet Hot American Summer, The 40-Year-Old Virgin, and Zack and Miri Make a Porno, she has also played Laura Bush in W. and the wife of Beach Boy Brian Wilson in Love and Mercy. As it turns out, one theme that threads across both the roles she has played and her own career arc is that of transformation. She is literally a two-time winner of the MTV Movie Award for Best On-Screen Transformation (2013, 2015) for her Hunger Games work.

Yet it is Banks’s role as producer and director of the Pitch Perfect films that most directly sets the stage for her DNC video. This role situates Banks as a powerful real world woman (an obviously more attractive association than Effie Trinket). The Pitch Perfect films focus on a barrier-breaking all-female club of collegiate a cappella singers (the Barden University Bellas) who compete in national competitions and become the “first all-female group to win a national title.” Banks’s acting role in the films is a small one; she plays a snarky smart commentator and an official who in Pitch Perfect 2 metes out punishment to the Bellas for a sexually explicit wardrobe malfunction during a White House performance. The film, however, sounds emotional chords that resonate in trial, transformation, and redemption for women in a competitive context.

This redemption is grounded in reclaiming group harmony—stronger together, as it were, which was perhaps the most prominent slogan at the Philadelphia convention. This reclamation becomes an American triumph in the final scene, as the ethnically, culturally, and personally diverse Bellas carry the USA banner in their quest to become the first American team ever to prevail in the international competition. Throughout that competition, their trendy (yet icy) German competitors mock the all-female group; however, after experiencing both personal and musical trials and ultimately transformation, the Bellas prevail in the World Championship. They open their performance with the lyrics “Who run the world? Girls!” from the Beyoncé song “Run the World (Girls),” a song included on Clinton’s Spotify playlist. In short, Pitch Perfect 2, with its narrative of competitive women who ultimately triumph through unity, provides a powerful metaphor for Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign.[vii]

Banks’ DNC video thus brings added layers to the complex image of Hillary Clinton. Musically, the a cappella version of “Fight Song” has the same feel as an original song composed by one of the Bellas in Pitch Perfect 2, a song that represents vulnerability, aspiration, and triumph, especially since original songs are a serious violation of competitive a cappella decorum. The lyrics of “Fight Song” reflect the voice of an underdog: “Like a small boat … like a single word … I might have only one match.” Clinton, of course, is the antithesis of the underdog in her quest for the Democratic nomination.

The underdog role might be more plausibly attached to Clinton as a woman seeking to become the first female president of the United States. Yet, the presidential politics of gender are clearly vexing, in particular when individual identity is seen as threatening to supersede national identity.[viii] How can Hillary Clinton simultaneously play the “woman card” while avoiding that move’s political baggage?[ix]

Perhaps because of the way it stakes out an independent stance, “Fight Song” lacks the narrative embrace of the whole of the nation represented in the Brooks & Dunn anthem “Only in America,” which featured prominently in Obama’s rallies in 2008: “Sun comin’ up over New York City … Sun goin’ down on an LA freeway … the promise of the promised land.” Even “Signed, Sealed, Delivered I’m Yours,” possibly the song most closely identified with Barack Obama’s 2008 bid, is a full-throated testimonial to devotion—and as such does not herald a group fight or crusade.[x] In this context, “Fight Song” has its strongest appeal in women’s struggle for equality, but does not explicitly invite others to embrace the struggle as an American struggle. It is “my fight song,” not “our” fight song. One can directly contrast “Fight Song,” the 2016 Clinton rally anthem, with Clinton’s 2008 use of “American Girl” by Tom Petty. Literally, America came first.

It is here where the audiovisual elements of the Banks video become transformative. The song is sung a cappella (the words “all sounds made by our voices” appear before the song begins). It is actually remarkable how effectively the percussion sounds are reproduced by human voices, which is the first turn toward a humanizing authenticity.

It is the visual elements of video, however, that most forcefully transform the song into a more universal anthem. The vast majority of individuals featured are gorgeous young celebrity women. Men might even be seen as gently teased in the video. The actor John Michael Higgins, who plays a boorish, sexist, racist oaf named John Smith in the Pitch Perfect films, is seen trying to horn in on the singing of the song and is bumped aside by Banks (Fig. 2).[xi] Yet the cumulative effect of each taking their turn singing the lead vocal (in a cappella competition fashion, where at points each member must carry the team) is to visually turn it from “my” fight song to “our” fight song. It should also be noted that there is a “rap” inserted two-thirds of the way through the video, speaking specifically to the historical nature of Clinton’s candidacy.

The turn toward the collective is amplified as the video reaches its climax. The frames featuring individual singers shrink to allow more and more singers to appear on the screen at the same time, until the frames begin to form a mosaic of the American flag. In Pitch Perfect 2, a similar visual approach (of individual members of the group isolated in separate frames pursuing their own agendas) is used in a scene to signify the fragmentation of the group into individual pursuits (Fig. 3). The DNC video, in contrast, emphasizes the unifying impact of the frames in the forming of the American mosaic (Fig. 4).

Such is the power of audiovisual communication and of politics. In the day-to-day coverage of campaigns, and indeed of American politics more broadly, the candidates and elected officials receive virtually all of the attention. Yet in a democracy, the citizens hold ultimate sovereignty. By turning the focus of attention away from Hillary Clinton and toward the millions who will vote for her, the Banks video fulfills the political promise of “Fight Song” that is lacking when the song stands alone as a rally anthem. Through audiovisual turn, “my fight song” becomes “our” fight song, thereby framing Clinton’s feminist quest as a transcendent human quest.

In Pulp Politics: How Political Advertising Tells the Stories of American Politics (Richardson 2008), I argue that campaign advertisements are able to draw upon the recognizable audiovisual conventions of popular culture to communicate messages to voters in terms with which they are already familiar. In 1988, prominent Bush-Quayle ads evoked the audiovisual conventions of horror films in their depiction of the “Nightmare on Elm Street” that would be America under a Dukakis presidency. In her DNC video, Elizabeth Banks draws upon the audiovisual conventions featured in the highest-grossing musical comedy in history to sketch out a feel-good narrative of trial, tribulation, transformation, and ultimate redemption of women in competition that helps remake Hillary Clinton’s “Fight Song” into a more universal fight song, indeed into America’s Fight Song, thus offering a powerful metaphor for the Clinton campaign.

– Glenn W. Richardson Jr.

REFERENCES

Barnard, Christianna. “Dancing Around the Double-Bind: Gender Identity, Likability, and the Musical Rebranding of Hillary Clinton.” Trax on the Trail, November 29, 2015. https://www.traxonthetrail.com/article/dancing-around-double-bind-gender-identity-likability-and-musical-rebranding-hillary-clinton.

Dewberry, David R., and Jonathan Millen. “Hillary Clinton’s 2016 Presidential Campaign Spotify Playlist.” Trax on the Trail, May 25, 2016. https://www.traxonthetrail.com/article/hillary-clinton%E2%80%99s-2016-presidential-campaign-spotify-playlist.

Diaz, Daniella. “Hillary Clinton Releases Spotify Playlist.” CNN, June 13, 2015. http://www.cnn.com/2015/06/13/politics/election-2016-hillary-clinton-spotify-playlist/.

Flegenheimer, Matt. “Clinton Woos a Crowd of Skeptics: White Men. Rust Belt Tour Seeks to Make Up Ground With the Population That Likes Her Least.” New York Times, August 2, 2016, A14.

Harris, Gardiner. “President Obama’s Emotional Spotify Playlist is a Hit.” New York Times, August 14, 2016. http://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/15/us/politics/president-obama-spotify-playlist.html?_r=0.

Kasperkevic, Jana. “Just One of the Cool Kids: Decoding the Hillary Clinton Spotify Playlist.” The Guardian, June 13, 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2015/jun/13/hillary-clinton-spotify-playlist.

Richardson, Glenn W. Jr. Pulp Politics: How Political Advertising Tells the Stories of American Politics. 2nd. ed. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2008.

Such, Courtney.

“Hillary Clinton Makes a Playlist.” RealClear Politics, June 15, 2015. http://www.realclearpolitics.com/articles/2015/06/15/hillary_clinton_makes_a_playlist_126985.html.

[i] I am grateful for the helpful suggestions of Jim Deaville and Dana Gorzelany-Mostak and for the conversations I had with Carolyn Gardner and Colleen Fitzgerald that have helped strengthen this effort.

[ii] This essay arrived on our desks before the hate fest over “Fight Song” reached fever pitch. For more on the kerfuffle, see Alex Garofalo, “Hillary Clinton’s ‘Fight Song’ Dragged by Twitter: Why People Hate The DNC Anthem,” International Business Times, July 29, 2016, http://www.ibtimes.com/hillary-clintons-fight-song-dragged-twitter-why-people-hate-dnc-anthem-2395852; Katie Kilkenny, “People Really, Really Hate ‘Fight Song.’ Could That Actually Hurt Clinton?” Pacific Standard, August 24, 2016, https://psmag.com/people-really-really-hate-fight-song-could-that-actually-hurt-clinton-cd5b8072cb33#.tuv32apo0; and Hunter Walker, “Hillary Clinton’s ‘Fight Song’ Is Driving Some People Nuts,” Yahoo! News, August 24, 2016, https://www.yahoo.com/news/fight-song-hillary-clinton-campaign-000000883.html.

[iii] “Democratic National Convention – Our Fight Song,” July 26, 2016, video clip, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YttscNOoAjA.

[iv] Like much of the Clinton playlist, “Fight Song” embraces the notion of the candidate as a fighter. For an in-depth thematic analysis of Clinton’s Spotify playlist, see David R. Dewberry and Jonathan Millen, “Hillary Clinton’s 2016 Presidential Campaign Spotify Playlist,” Trax on the Trail, May 25, 2016, https://www.traxonthetrail.com/article/hillary-clinton%E2%80%99s-2016-presidential-campaign-spotify-playlist.

[v] Mrs. Clinton has the unenviable task of following Barack Obama, whose Spotify playlists are not seen as reflecting popular culture but rather shaping it. Obama’s 2016 “Summer” Spotify playlist almost immediately “… was the most listened-to on Spotify, other than those organized by the global music streaming service itself.” See Gardiner Harris, “President Obama’s Emotional Spotify Playlist Is a Hit,” New York Times, August 14, 2016, http://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/15/us/politics/president-obama-spotify-playlist.html?_r=0.

[vi] Author’s transcription of C-SPAN video (03:06:50 minute mark). See “Democratic National Convention,” uploaded July 26, 2016, video clip, CSPAN, https://www.c-span.org/video/?412846-1/hillary-clinton-officially-nominated-democratic-presidential-nominee&start=11089.

[vii] The Bellas even overcome a White House “sex” scandal.

[viii] See Christianna Barnard, “Dancing Around the Double-Bind: Gender Identity, Likability, and the Musical Rebranding of Hillary Clinton,” Trax on the Trail, November 29, 2015, https://www.traxonthetrail.com/article/dancing-around-double-bind-gender-….

[ix] In April 2016, Clinton responded to Trump’s claim that she was playing the woman card with the following remark: “Well, if fighting for women’s health care and paid family leave and equal pay is playing the woman card, then deal me in!”

[x] In Pitch Perfect 2, the Bellas get their groove back and rediscover team harmony through the sounds of Motown. Motown grooves may have aided Clinton as well. Shortly after the convention, she embarked on a Rust Belt bus tour with vice presidential nominee Tim Kaine. Matt Flegenheimer of the New York Times reported that she “was now taking the stage to a Motown classic ‘Ain’t No Mountain High Enough,’ sidelining a rotation of female pop stars.” See Matt Flegenheimer, “Clinton Woos a Crowd of Skeptics: White Men. Rust Belt Tour Seeks to Make Up Ground With the Population That Likes Her Least,” New York Times, August 2, 2016, A14. By late August, the Marvin Gaye/Tammi Terrell classic was used at the conclusion of Clinton’s own events, exactly as “Fight Song” had been during the primaries.

[xi] Comedians Stephen Colbert and John Oliver released a parody of Banks’s video that doubled-down on the notion of boorish male behavior. The comedians appear in frames in the video, including one where, interestingly enough, Oliver describes not being told he was going to appear in “this weirdly earnest a cappella song for Clinton.” See “The Late Show’s ‘Fight Song’ feat. John Oliver,” uploaded July 28, 2016, video clip, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NONMleUjZ04.