August 24, 2016

In US electoral politics since the 1980s, many candidates have (re-)branded themselves as “hip” and “cool” by utilizing hit songs from mainstream popular music. As a significant example of this trend during the 1992 US presidential election, Bill Clinton mobilized MTV culture by using classic rock, with Fleetwood Mac’s “Don’t Stop” serving as his campaign’s theme song. Recent scholarship has contextualized how political campaigns harness pop music’s lyric and sonic attributes to attract constituencies diverse in age, race, class, and gender (Sterne 1999; Schoening and Kasper 2012; Love 2015 and 2016; Gorzelany-Mostak 2015 and 2016).

In this era of musically “cool” political spectacles, the folk expression of one of America’s most politically active musicians, Woody Guthrie (1912–1967), has persevered. The singer-songwriter used his art and ideals to fight inequality, persecution, and bigotry amidst the Great Depression, World War II, the Cold War, and the Civil Rights Movement. Influenced by prairie radicalism, the Oklahoman championed the working class and spread his socialist ideology throughout US urban centers during the nascence of America’s folk revival in the 1940s (Kaufman 2011). Following a career shortened by Huntington’s disease in 1952, Guthrie’s popularity grew in the 1950s and 1960s through the efforts of his contemporaries and the subsequent generation of folk musicians, including Pete Seeger, Jack Elliott, and Bob Dylan (Cohen 2012, 2–3). Written in 1940 and first recorded in 1944, Guthrie’s celebrated “This Land Is Your Land” has become a popular fixture in US electoral politics. Contributing to the reception histories of both song and artist, this essay examines the myriad ways that “This Land Is Your Land” and Guthrie’s working-class heroism have impacted political discourse during the 2015–16 campaign cycle.

Guthrie wrote “This Land Is Your Land” as a protest song to counter Irving Berlin’s “God Bless America” (1938), which Guthrie hated for its sanctimonious and jingoistic themes as well as its ignorance of true working-class experiences (Kaufman 2011, 28–29).[i] “This Land Is Your Land” now exists in several versions, which evoke different interpretations. First copyrighted in 1956, the song’s complete lyrics comprise a chorus-refrain plus six verses that portray complex images of the nation—some regard its idyllic natural beauty, while others concern its deplorable class oppression. In the 1950s, schools and church organizations presented “This Land Is Your Land” in recordings and publications, but diluted the song’s message by omitting its protest lyrics and retaining only the three idyllic verses and refrain. This sanitized version became the standard patriotic anthem in the public’s consciousness, much to Guthrie’s dissatisfaction (Jackson 2002, 260–64). Continuing Guthrie’s legacy, fellow folk musician and political activist Pete Seeger (1919–2014) consistently performed “This Land Is Your Land” in its complete version with the protest verses included (with occasional variances in order and wording). However, the efforts of Seeger and other folk artists have not dethroned the song’s standardized, politically eviscerated form.

The song’s origins in protest illuminate its radically socialist intent, which sometimes coincides with and at other times contradicts its political usage. “This Land Is Your Land” served as a central theme song in the presidential campaigns of Democratic candidate Robert F. Kennedy in 1968 and Republican nominee George H.W. Bush in both 1988 and 1992. Kennedy employed the song’s entire message, which accorded with the candidate’s liberal platform of economic equality and racial reconciliation and justice (Schoening and Kasper 2012, 147–48). In contrast, in order to court moderate middle-class voters, Bush’s use of “This Land Is Your Land” focused on the song’s refrain and hook to promote a narrative of prosperity while aligning the candidate with the filtered public perception of Guthrie as a patriotic American artist. However, Bush’s narrative ignored the folk icon’s communist leanings and condemnation of the upper class and conservative ideology, thus exemplifying the possible misrepresentation of a song’s meaning through its appropriation (Schoening and Kasper 2012, 170–71, 181, and 225).

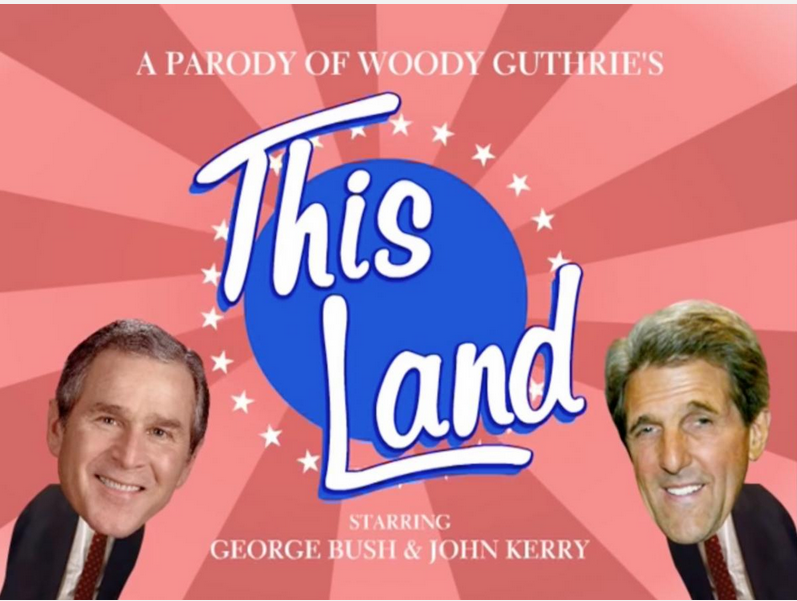

During the 2004 US presidential race, “This Land Is Your Land” affected both liberal and nonpartisan political discourse. Democratic nominee John Kerry occasionally participated in and played guitar for sing-alongs of the song, which denoted different ideologies depending on the venue. At his Midwestern campaign stops, the song functioned in its popular American anthem form to attract rural voters and eradicate Kerry’s aloof, elitist persona (Toner 2004). Yet at his July 8, 2004 celebrity fundraiser at Radio City Music Hall, the event’s anti-conservative rhetoric reinvigorated the song’s ultra-liberal interpretation in a sing-along led by John Mellencamp, Dave Matthews, John Fogerty, and Jon Bon Jovi (Crandall 2004). But the most celebrated use of Guthrie’s song during the 2004 election cycle occurred through its parody titled “This Land!”—a Flash animated video created and released online by the digital entertainment studio JibJab. This parody featured cutout animated figures of Kerry and George W. Bush singing alternate lyrics that attacked each other’s perceived flaws and utilized the new refrain “This land will surely vote for me.” Praised for its humorous, nonpartisan ridicule of the two candidates, JibJab’s video quickly became a viral hit and appeared on several major news outlets, including CNBC, Fox News, CBS’s The Early Show, and NBC Nightly News (Lohr 2004).[ii]

Guthrie’s leftist intentions for “This Land Is Your Land” were fully realized on January 18, 2009, in Washington D.C. at Barack Obama’s pre-inauguration We Are One concert, where Seeger, alongside Bruce Springsteen and a large choir, led an audience of more than 400,000 in a rousing performance of the song.[iii] Once again, Seeger included the oft-forgotten protest lyrics, and as Mark Pedelty suggests, this seminal event provided progressive activists a “unifying sense of hope and national identity” (Pedelty 2009, 426).

In apparent attempts to recapture the 2009 optimism for their Democratic party, Maryland Governor Martin O’Malley and Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders extensively incorporated “This Land Is Your Land” into their 2015–16 US presidential campaigns. The song not only aligned with O’Malley’s concern for working-class well-being, but it also provided him an opportunity to demonstrate his strong musical background.[iv] Proficient on guitar and vocals, O’Malley performed Guthrie’s song, among other favorites, at many of his campaign stops, and the “troubadour” candidate frequently included the song’s additional protest lyrics (see Brian Barone’s Trax article). Often inviting audience participation, O’Malley’s live performances may have recalled the 2009 We Are One concert while also providing nostalgia for his constituency by simulating group singing in the mode of the mid-twentieth-century folk revival. However, O’Malley’s efforts failed to generate enough optimism and support to propel him past the first caucus.

Sanders’s fervent working-class and socialist platform strongly corresponded to Guthrie’s ideals and music, which the candidate reified with his publicized visit to the Woody Guthrie Center in Tulsa in late February 2016. From his campaign launch on May 26, 2015 to his reluctant endorsement of opponent Hillary Clinton in July 2016, “This Land Is Your Land” served as a theme song for Sanders, who already had an association with the song. Collaborating with other folk artists while he was mayor of Burlington, Vermont, Sanders recorded a cover of “This Land Is Your Land” for his 1987 folk album We Shall Overcome, which features five protest songs of the Civil Rights Movement popularized by Odetta, Guthrie, and Seeger. We Shall Overcome garnered little attention before its remastering and re-release in December 2014 (Stuart 2015).

While “This Land Is Your Land” did not appear on Sanders’s campaign playlist, the song served multiple purposes on his presidential campaign trail: it appeared in videos created by artists who support the candidate and in the programs of tribute concerts and rallies, which provided launching points for interactive sing-alongs. In these live settings, musicians led the performances while Sanders faded in and out with his vocals, such as at a January 30, 2016 Iowa City rally featuring Vampire Weekend, as well as at Sanders’s March 1, 2016 Super Tuesday celebration in Essex County, Vermont with Kat Wright and the Indomitable Soul Band. Depending on the lead singers’ familiarity with the song’s little known protest lyrics, the performances occasionally presented the song in its complete form. Furthermore, the various renditions of “This Land Is Your Land” during Sanders’s campaign comprised a wide variety of musical styles, including folk, indie, hard rock, soul, and reggae. This strategy espoused cultural diversity—manifesting Guthrie’s belief in the integration of black and white working-class cultures, while countering perceptions of Guthrie that consider him to only represent the white working class (Garman 2000, 3–4 and 11–13).

Community singing and dancing allowed Sanders to participate in the song’s expression while hiding his limited musicality and speech-singing (or quasi-barking) vocalizations, reminiscent of his 1987 recording. But these interactive performances also typify Christopher Small’s concept of “musicking,” which challenges scholarly assumptions that music is solely an object or self-contained work. As Small suggests, musicking “is to take part, in any capacity, in a musical performance, whether by performing, by listening, by rehearsing or practicing, by providing material for performance . . . or by dancing” (Small 1998, 9). Musicking denotes activities or rituals that create sonic and physical music scenes in which social relationships are formed: “relationships between person and person, between individual and society, between humanity and the natural world and even perhaps the supernatural world” (Small 1998, 13). And these relationships provide essential musical meaning by defining both individual and social identities (Small 1998, 41–47 and 130–34).

Translating Small’s theories to the political realm, Sanders’s sing-alongs of “This Land Is Your Land” promoted themes of community, nostalgia, and equality for middle- and lower-class America. Through musical interaction at campaign rallies and concerts, Guthrie’s anthem sonically authenticated Sanders’s socialist platform while providing his supporters the experience of physically enacting the candidate’s message. Simultaneously, the musicking rituals on both O’Malley’s and Sanders’s campaign trails helped to restore the song’s radical leftist, working-class origins. In these cases, music solidified political identities within a community of individuals who were united in their political beliefs and actions, thus illustrating how campaign music operates both as an expression of political causes as well as a cause of political expression (Street 2011, 170–73).

“This Land Is Your Land’s” presence in the remaining US presidential race will probably subside, with both O’Malley and Sanders now out of contention. Yet, Guthrie’s leftist radicalism may still serve as an opponent to conservatism leading up to November’s election, such as it did in early 2016 when the national media pitted the folk icon’s tenets for racial and economic equality against Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump. Folk music and Guthrie scholar Will Kaufman’s archival research determined that Fred C. Trump, Donald’s father, was Guthrie’s landlord in early 1950s Brooklyn (Kaufman 2016). As a developer of urban public housing in the postwar years, Fred Trump frequently faced accusations of profiteering and racial discrimination—the former led to a US Senate committee investigation in 1954, while the latter ultimately resulted in two civil rights cases brought against the Trump real estate empire by the US Justice Department in 1973 and 1978 (Kaufman 2016). Among the documents Kaufman discovered were Guthrie’s writings that lament “Old Man Trump’s” unethical and bigoted practices, including welcoming only white tenants, while Guthrie imagined an integrated community with “a diverse cornucopia” of races and ethnicities (Kaufman 2016). Stimulated by Kaufman’s findings, American news outlets mapped Fred Trump’s background onto Donald Trump’s campaign and used Guthrie’s ideals as a means to censure the Republican candidate’s racially-charged rhetoric.

On July 12, 2016, in hopes to unify Democrats, Sanders endorsed Hillary Clinton as their party’s presidential nominee (Alcindor, Chozick, and Healy 2016). However, there is little evidence that Clinton will assimilate Sanders’s fondness for Guthrie, who is not without controversy regarding gender politics. Guthrie’s perceived sexism has blemished his legacy, as he abandoned his domestic responsibilities and exploited his female relationships while becoming “America’s favorite hobo” (Kaufman 2011, xxii). Associating herself with this perception would be counterintuitive for Clinton’s feminist platform. Moreover, Clinton’s campaign playlist strategically has signified gender diversity and feminine strength through contemporary artists, leaving little room for Guthrie’s music to affect the remaining election cycle (see Christianna Barnard’s and David Dewberry and Jonathan Millen’s Trax articles). Yet, in numerous instances that have connected Guthrie’s working-class heroism with political discourse, the 2015–16 US presidential race has demonstrated that Guthrie and his music could be politically “cool” once again.

– Michael Kennedy

Bibliography

Alcindor, Yamiche, Amy Chozick, and Patrick Healy. “Bernie Sanders Endorses Hillary Clinton, Hoping to Unify Democrats.” New York Times, July 12, 2016.

Barnard, Christianna. “Dancing around the Double-bind: Gender Identity, Likability, and the Musical Rebranding of Hillary Clinton.” Trax on the Trail, November 29, 2015.

Barone, Brian. “‘I’ve Been Everywhere’: Martin O’Malley and the Many Meanings of the Guitar.” Trax on the Trail, January 8, 2016.

Blim, Richard Daniel. “Patchwork Nation: Collage, Music, and American Identity.” PhD diss., University of Michigan, 2013.

Chokshi, Niraj. “Who Owns the Copyright to ‘This Land Is Your Land’? It May Be You and Me.” New York Times, June 17, 2016.

Cohen, Ronald D. Woody Guthrie: Writing America’s Songs. New York: Routledge, 2012.

Crandall, Bill. “DMB, Blige Rock for Kerry.” Rolling Stone, July 9, 2004.

Dewberry, David R., and Jonathan Millen. “Hillary Clinton’s 2016 Presidential Campaign Spotify Playlist.” Trax on the Trail, May 25, 2016.

Garman, Bryan K. A Race of Singers: Whitman’s Working-class Hero from Guthrie to Springsteen. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2000.

Gorzelany-Mostak, Dana. “‘I’ve Got a Little List’: Spotifying Mitt Romney and Barack Obama in the 2012 US Presidential Election.” Music & Politics 9, no. 2 (2015).

_____. “Keepin’ It Real (Respectable) in 2008: Barack Obama’s Music Strategy and the Formation of Presidential Identity.” Journal of the Society for American Music 10, no. 2 (2016): 113–48.

Jackson, Mark Allan. “Is This Song Your Song Anymore?: Revisioning Woody Guthrie’s ‘This Land Is Your Land.’” American Music 20, no. 3 (2002): 249–76.

Kaufman, Will. Woody Guthrie, American Radical. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2011.

_____. “Woody Guthrie, ‘Old Man Trump,’ and a Real Estate Empire’s Racist Foundations.” The Conversation, January 21, 2016.

Lohr, Steve. “A Duet That Straddles the Political Divide.” New York Times, July 26, 2004.

Love, Joanna. “Branding a Cool Celebrity President: Popular Music, Political Advertising, and the 2012 Election.” Music & Politics 9, no. 2 (2015).

_____. “Political Pop and Commercials That Flopped: Early Lessons from the 2016 Presidential Race.” Trax on the Trail, January 14, 2016.

Pedelty, Mark. “This Land: Seeger Performs Guthrie’s ‘Lost Verses’ at the Inaugural.” Popular Music and Society 32, no. 3 (2009): 425–31.

Schoening, Benjamin S., and Eric T. Kasper. Don’t Stop Thinking about the Music: The Politics of Songs and Musicians in Presidential Campaigns. Lanham, MD: Lexington, 2012.

Small, Christopher. Musicking: The Meanings of Performing and Listening. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1998.

Sterne, Jonathan. “Going Public: Rock Aesthetics in the American Political Field.” In Sound Identities: Popular Music and the Cultural Politics of Education, edited by Cameron McCarthy, Glenn Hudak, Shawn Miklaucic, and Paula Saukko, 289–315. New York: Peter Lang, 1999.

Street, John. Music and Politics. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2011.

Stuart, Tessa. “The Untold Story of Bernie Sanders’s 1987 Folk Album.” Rolling Stone, December 2, 2015. http://www.rollingstone.com/politics/news/the-untold-story-of-bernie-sanders-1987-folk-album-20151202.

Toner, Robin. “With Guns and Butter, Kerry Woos Rural Voters.” New York Times, July 4, 2004. http://www.nytimes.com/2004/07/04/us/the-2004-campaign-the-senator-with-guns-and-butter-kerry-woos-rural-voters.html.

Wagner, John. “Songs of ‘Revolution’ and Others That Make Bernie Sanders’s Playlist.” Washington Post, February 8, 2016.

[i] Guthrie’s original 1940 version of the song was titled “God Blessed America,” with the refrain “God blessed America for me,” which emphatically situated “God’s blessing” of the nation in the past tense while locating America’s struggles in economics and politics. When Guthrie recorded the song in 1944, he changed the title to “This Land Is Your Land” and the refrain to “This land was made for you and me,” focusing on the song’s message of equality (Jackson 2002, 249–50).

[ii] In June 2004, Ludlow Music, the publishing company that controls the rights to “This Land Is Your Land” on behalf of the Richmond Organization, threatened JibJab with a copyright lawsuit for the unauthorized use of Guthrie’s music. In response, JibJab sued Ludlow in July 2004 to obtain federal judicial confirmation that their work was protected as “fair use” and did not transgress Ludlow’s copyright. The two sides reached a settlement after JibJab’s lawyers claimed that the song’s original copyright from 1945 actually expired in 1973, which Ludlow failed to renew since it had filed its own copyright of the song in 1956 (Chokshi 2016).

[iii] For more on the We Are One concert, see Trax contributor Richard Daniel Blim’s dissertation, “The Electoral Collage: Mapping Barack Obama’s Mediated Identities in the 2008 Election,” chap. 5 in “Patchwork Nation: Collage, Music, and American Identity” (PhD diss., University of Michigan, 2013).

[iv] O’Malley’s presidential candidacy began on May 30, 2015, and it ended on February 1, 2016 after the Iowa caucus. Exemplifying his musical background, O’Malley has frequently performed guitar, banjo, and lead vocals for the Baltimore-based Celtic-rock band O’Malley’s March, which he founded in 1988.