March 31, 2016

On 13 January 2016, approximately 12,000 people gathered in the Pensacola Bay Center in Pensacola, Florida for a two hour rally in support of Republican presidential candidate Donald J. Trump. At an event that included the Gun Girls for Trump leading the pledge of allegiance, speeches from local Trump supporters, and an hour-long speech by the man himself, one two-and-half minute segment caught the nation’s attention: a performance by the group USA Freedom Kids of “Freedom’s Call,” a version of George M. Cohan’s “Over There,” rewritten by the group’s manager (and father of one of the performers) Jeff Popick. The performance has drawn strong reactions from both sides of the political spectrum. One commenter on the Conservative news site Breitbart.com under the alias “sgstandard” called the performance “uplifting, patriotic and inspiring,” while “Media Mole,” writing for the Liberal UK publication NewStatesman said the number was “an unsettling and horrifying spectacle.”

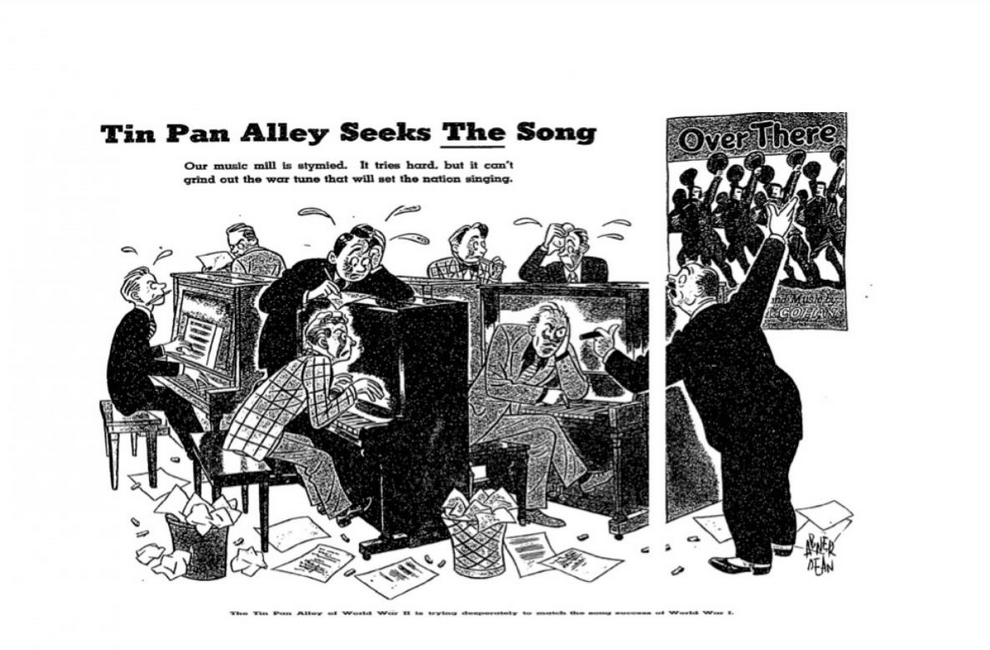

“Over There,” has a fascinating history, one that says a great deal about Trump’s campaign. Cohan is a Broadway legend, a writer/director/producer/singer/dancer/actor whose red-white-and-blue-drenched patriotic spectacles played to thousands in the first quarter of the twentieth century (Fig. 1). These spectacles gave us patriotic staples such as “The Yankee Doodle Boy” and “You’re a Grand Ol’ Flag” (these clips are from a colorized version of Yankee Doodle Dandy, a 1942 biopic starring James Cagney as Cohan.) As Raymond Knapp has observed, Broadway musicals are “an enacted demonstration of Americanism, and often take on a formative, defining role in the construction of a collective sense of ‘America’” (103). Political rallies can serve a similar purpose, with candidates using these events to define and construct a collective sense of nation through a mix of spectacle, participation, and policy. In this light, the appearance of “Over There” at a Trump rally can be considered as an “enacted demonstration” of the kind of America the candidate hopes to create. The song’s marching rhythms and bugle-call chorus along with its unequivocally pro-America and pro-War messages (in both the 1917 and 2016 versions) point to an America in which patriotism is paramount and a strong military presence defines the country’s role on the national stage. There is also something highly nostalgic about Trump’s campaign. His slogan, “Make America Great Again” (emphasis added), implies the need to return to the policies that made America great historically, but which present leaders have abandoned. Even if the audience did not recognize the tune, the song itself—its simple rhythms, clear harmonies, and easily singable melody—sounds old-fashioned and is reminiscent of other Cohan songs attached to Broadway shows, even though “Over There” was not written for a specific show. Generally speaking, Broadway carries the connotation of nostalgia (Rugg, 45ff).

But what kind of America does Trump want to bring back? Again, “Over There” is telling. Cohan wrote “Over There” in 1917 as part of the effort to unite the country behind President Woodrow Wilson’s entry into World War I (McCabe, 137–138). The song was so influential during World War II that the Office of War Information searched for a similar song to inspire the public to support that war (Smith, 3). But the sunny patriotism and catchy tune of “Over There” also provided the soundtrack for an outbreak of anti-foreign sentiment that boiled over into violence on several occasions between 1917 and 1919. Trump’s campaign has a similarly aggressive undercurrent that has earned the candidate much criticism. In other ways, however, the appearance of “Over There” at a Trump rally is historically incongruous, particularly in light of Trump’s anti-immigration platform. The Irish Cohan was only third-generation American (McCabe, 3).

“Over There” was popular at a number of World War I rallies and benefits, performed by stars ranging from the popular singer Nora Bayes to the opera star Enrico Caruso, and even occasionally, Cohan himself. These rallies presaged Trump’s modern political events: they were often held in theatres or stadiums, with a mix of speakers (often veterans) and performers, and strewn with flags and banners. For example, the Trump rally that included the USA Freedom Kids’ performance also had speeches by a local member of the National Rifle Association and three veterans. Furthermore, speakers at both World War I and Trump rallies have harsh words for America’s enemies. Just as Trump promised in Pensacola to take a hard line negotiating with Iran, China, and Mexico, one-time gubernatorial candidate Job E. Hedges told the crowd at a Saratoga, NY World War I benefit, “There can be no place for Germany at the peace table,” decrying the state of “German-Kultur” as “an overestimate of the of the mind at the expense of the soul,” and even claiming that “Germany has no soul.”[i] That evening also featured a performance of “Over There,” in this case by Caruso.

But more than the rallies themselves, Trump’s forceful rhetoric and calls for vigilance on the home front echo the national climate between 1917 and 1919. Both Trump supporters and over-enthusiastic citizens during World War I resorted to violence against perceived enemies in the name of patriotism. Numerous incidents have broken out at Trump’s events, and the candidate has faced criticism for his response. He declined to condemn supporters who attacked a homeless Latino man in August, merely saying “I will say that people who are following me are very passionate. They love this country and they want this country to be great again.” Popick’s lyrics “come on boys, take ‘em down!” seem to tacitly encourage this attitude. At the same Pensacola rally, Trump condemned the neighbors of the San Bernardino shooters for not speaking up sooner, blaming political correctness for their failure to report suspicious behavior and thus echoing politicians during World War I who asked Americans to remain alert to foreign agents or ideas that may have insinuated themselves into American culture (Capozzola, 1360). But many went beyond vigilance to vigilantism in the name of patriotism. On 12 July 1917 in Bisbee, Arizona, a local vigilance society deported striking miners and their families to New Mexico at gunpoint on the grounds that their demands for better working conditions were unpatriotically damaging the war effort (bullets required copper) (Capozzola, 1365–66). Some vigilance societies even went so far as to lynch German-Americans (Jones, 50). Like Popick’s lyrics, Cohan’s text to “Over There” could be read as encouraging this; the opening line “Johnny get your gun, get your gun, get your gun” was intended as a call for enlistment, but could just as easily be understood as a general call for all Americans to participate.

But the anti-foreigner sentiment of Trump’s campaigns also clashes with “Over There.” George M. Cohan was a proud third-generation Irish-American, who openly celebrated his immigrant background. Cohan got his professional start performing in his father’s Irish novelty act called “Jerry Cohan’s Irish Hibernia” (Cohan, 14), and along with his patriotic numbers, wrote songs like “Mary’s a Grand Old Name” and “Harrigan,” making no secret of his heritage (Jones, 22). In 1921, he even hosted a fundraiser given by the American Committee for Relief in Ireland, helping to raise $57,000 for the cause of Irish freedom,[ii] hoping that Ireland would break free of Great Britain’s government just as America had 150 years earlier.

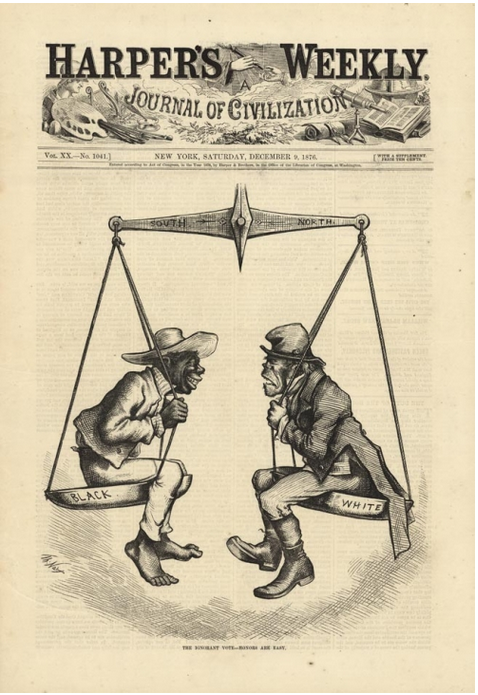

While Cohan vocally proclaimed his Irishness and his Americanness on Broadway stages around the turn of the century, making it clear that he found no contradiction between the two, a massive debate over immigration was raging in the larger culture. Anti-immigration activists of the era shared many of the same concerns as today’s Trump supporters. Not only were they worried about the influx of labor and the subsequent wage stagnation, but broader concerns about the future of the nation also percolated beneath the surface. When Trump said of Mexican immigrants, “They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists,” he echoed stereotypes from earlier times that were applied to the Irish—that they were mostly criminals who preyed on unsuspecting Americans. For example, in 1876, the cover of Harper’s Weekly depicted a stereotypical pugnacious looking Irish-man weighed on a scale against a Jim Crow-like African American with the two sides equally balanced—not a compliment at the time (Fig. 2). Although by Cohan’s time, the “Celtic” race, as the Irish were called at the turn of the century, was preferable to other Eastern European races in anti-immigration circles, the so-called NINA restriction (“No Irish Need Apply”) in job advertisements still appeared occasionally during the late 1910s (Fried 3–4). More strikingly, some activists in the late 19th and early 20th centuries even proposed limiting immigration based on religion, believing “Papist” (Catholic) Celts were not fit to participate in American democracy because they were beholden to Rome (Jacobson 69–70). Trump’s proposed ban on Muslim immigrants (and former candidate Ben Carson’s claim that Islam is “inconsistent” with the Constitution) looks very similar in some respects.

If musical theater—whether on a Broadway stage or a political rally—is an “enacted demonstration of Americanism,” then the appearance of a version of “Over There” at a Trump rally appropriately demonstrates the kind of America that Trump is proposing. In both Trump’s America and the America of World War I, patriotism is the greatest national virtue, and citizens must always be alert to the danger of foreign threats. However, there is a certain irony in the performance of “Over There” at a Trump rally given that, had policies similar to Trump’s been in place in the 19th century, Cohan’s grandparents would never have come to America, and “Over There” would never have been written.

– Naomi Graber

Bibliography

Capozzola, Christopher. “The Only Badge Needed is Your Patriotic Fervor: Vigilance, Coercion, and the Law in World War I America.” Journal of American History 88, no. 4 (2002): 1354–1382.

Cohan, George M. Twenty Years on Broadway and the Years It Took to Get There: The True Story of a Trouper’s Life from the Cradle to the “Closed Shop.” New York and London: Harper & Brothers, 1925.

Fried, Rebecca A. “No Irish Need Deny: Evidence for the Historicity of NINA Restrictions in Advertisements and Signs.” Journal of Social History (2015): available online at http://jsh.oxfordjournals.org.proxy-remote.galib.uga.edu/content/early/2015/07/03/jsh.shv066.full.pdf+html.

Jacobson, Matthew Frye. Whiteness of a Different Color: European Immigrants and the Alchemy of Race. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998.

Jones, John Bush. Our Musicals, Ourselves: A Social History of American Musical Theater. Hanover, NH: Brandeis University Press, 2003. Kindle Edition.

McCabe, John. George M. Cohan: The Man Who Owned Broadway. Garden City, NJ: Doubleday, 1973.

Knapp, Raymond. The American Musical and the Formation of National Identity. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005.

Rugg, Rebecca

Ann. “What it Used to Be: Nostalgia and the State of the Broadway Musical.” Theater 32 no. 2 (2002):

44–55.

[i] “4,302,000 Raised at Big Loan Concert,” New York Times, 1 October 1918, p. 11.

[ii] “Stage Stars Raise $57,000 for Irish,” New York Times, 4 April 1921, p. 2.