Our project on pop

songs and political campaigning began in the fall of 2015, when we decided to

work on a campaign music article that we could present at the Music and

Entertainment Industry Educators Association (MEIEA)

Conference in April 2016. We thought that it was especially appropriate, since

the conference that year was to be held in Washington, D.C. We started

following the 2016 presidential elections by both paying close

attention to the music selected by presidential hopefuls and tracking the

reactions of the artists whose music was being used (in some cases, without

their permission). Our focus was commercially produced songs, which spanned

many genres and were played at a campaign event such as a rally, fundraiser,

stop on the trail, or convention. We did not focus specifically on music used

in campaign advertisements on television or Internet per se, although we

identify some of this music in the full article. The April conference came, and

we presented some of our initial findings to a large audience, followed by a

robust Q&A session. This feedback encouraged us to go back a few election

cycles to dig deeper and document trends in candidate usage, if such trends

were to be identified. The main challenge for our project was the development

of a methodology. How could we document trends over four election cycles when

we collected both numerical and qualitative data? We ultimately settled on a

hybrid approach, combining traditional statistics with non-linear Social

Network Analysis (SNA) that has the potential to document the social

connections between candidates, targeted voters, and musical genres. (We

address the parameters of SNA in more depth in our full article which appears

in the Journal for Popular Music Studies.)

Thus, our full article, “Pop Songs on Political Platforms,” investigates popular music usage in the campaigns of American presidential candidates from 2004 to 2016. Using both numerical and qualitative data, we established certain criteria for each candidate to assess whether connections existed between party affiliation, age and other demographic information for the candidates, song details for the music selected (with title, performer, copyright year, and genre), demographics of targeted voters, cease and desist order/copyright infringement allegations, and resulting success in polls.

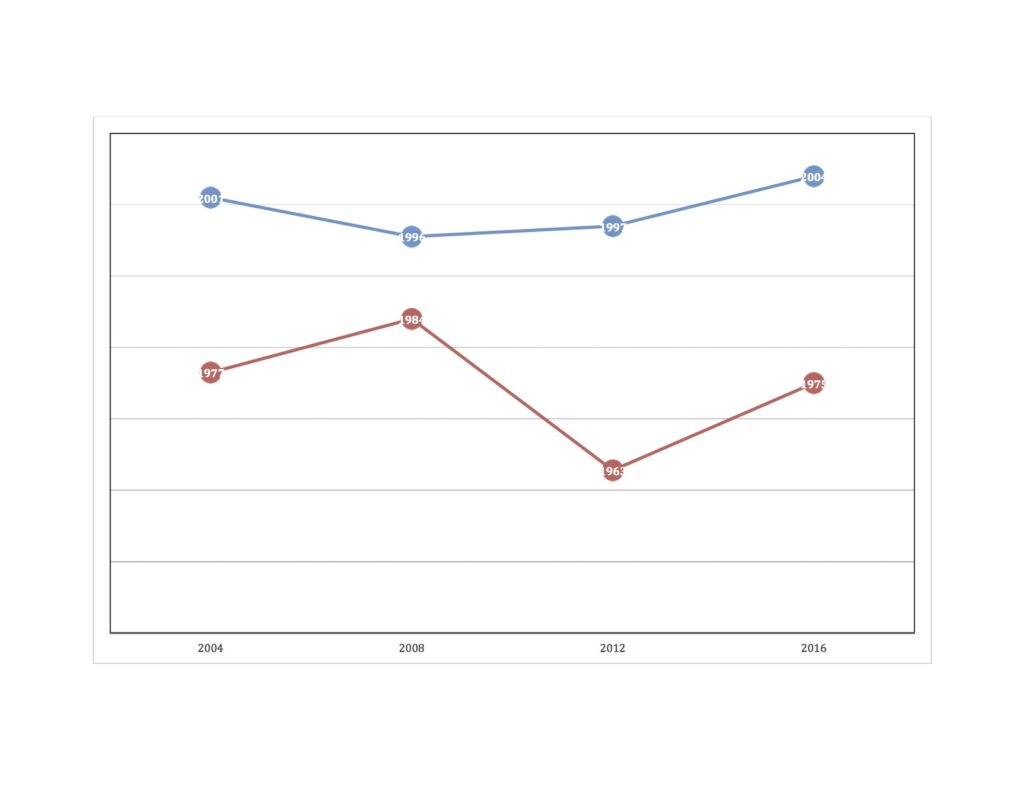

We presented visual outputs of the data in the form of networks. When numerical data was available (i.e., age of candidates and copyright year), linear statistics such as scatter diagrams or line graphs were the best tool to present correlations and trends. In order to show emerging patterns and behaviors using qualitative data, SNA was employed.

This mixed methodology allowed us to explore the following research questions:

- Is there a correlation between the age of presidential hopefuls and copyright years of songs selected for their campaigns?

- What are some of the emerging patterns between demographic data of presidential hopefuls (age, ethnicity, sex, and religion) and the music genre(s) of the songs selected for their campaigns?

- How can we determine the correlation between the candidates’ party affiliation and artists’ claims of copyright infringement?

- Is there a specific connection between the music genres selected by the campaigns and the demographics of their targeted voters?

- How significant is the number of songs and music genres used in campaigns and does the size or diversity of a candidate’s playlist affect the election results? Is there a correlation between the average copyright years of the music selected and election results?

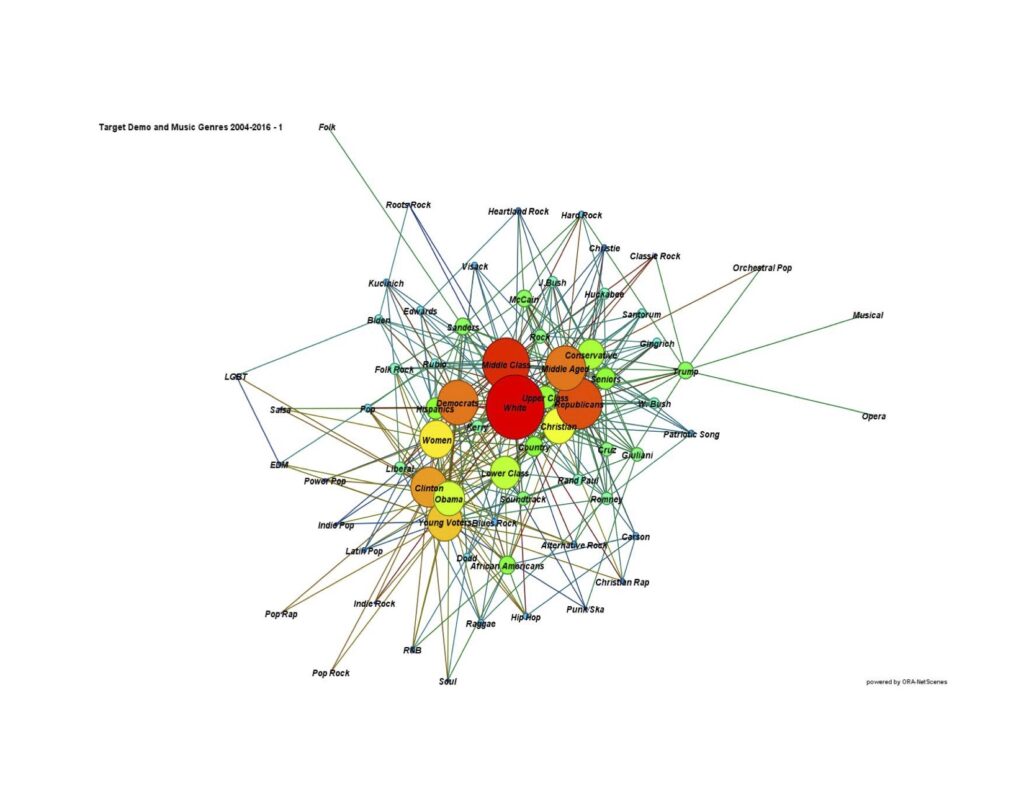

Our research model was an effective one, and we were able to reveal patterns and document them throughout our study. We observed that younger presidential candidates, Republicans and Democrats alike, tended to select pop songs copyrighted more recently (21st century), whereas older candidates preferred songs that appealed to an older, white target voter demographic (mostly rock spanning from the 1960s to the early 1990s). Still, Democratic candidates draw upon a more diversified, broader selection of music than their Republican counterparts. (See Appendix I for a list of titles and their genre designation.) Most presidential candidates appear to be white males in their early to mid-60s who are prominently Roman Catholics. United Methodists and Southern Baptists are the other two religious affiliations well represented amongst presidential hopefuls. Rock music is the most popular music genre selected, followed closely by alternative rock, country music, and hard rock. The most common music genres shared by Republican and Democratic voters are rock and country music, but Republican candidates have used country music, patriotic songs, and heartland rock (rock music featuring themes associated with struggles of “ordinary” Americans) in addition to hard rock, classic rock, and orchestral pop to target their mostly white Christian and middle-aged voters. Rock, pop, Latin pop, blues rock, indie pop, salsa, soul, and R&B are the genres mostly used to target African American and Hispanic voters. Also, EDM has been associated with LGBT voters as well as with young voters. Lastly, women voters are closely linked to pop and rock music.[i] (See Figure 1 for a visual depiction of music genres and target voters.)

We observed that Republican candidates were most likely to be accused of copyright infringement and/or subject to opposition from artists in the 2008, 2012, and 2016 presidential campaigns. However, the findings suggested that there does not seem to be a clear pattern showing a connection between the age of the presidential candidates and copyright infringement. Since 2004, the Democratic presidential candidates have consistently used a larger pool of songs and a wider diversity of music genres in their campaigns. Conversely, on the Republican side, candidates have consistently used approximately the same sized portfolio of songs and music genres. Candidates who have won the popular vote during their race for the presidency since 2004 have had a more recent copyright year for the songs they have used, whereas unsuccessful candidates, on average, selected older songs (Fig. 2).[ii] And for the past three election cycles, the Democratic candidates were the ones to formulate such a music strategy for their campaigns. However, we are seeing an increase in song usage on the Republican side.

Thus, the dramatic increase in popular song usage is apparent just in reviewing four presidential campaign cycles within this study. We believe the Internet will continue to open new avenues for music usage in campaigns, even by individuals not officially associated with candidates. Furthermore, the innovative ways candidates will continue to use music in their campaigns remains to be seen. This study of pop songs on political platforms is particularly important because of the positive correlations discovered between the higher quantity and variety of music used, more recent copyright year, and election or securing the popular vote (in the case of Hillary Clinton in the 2016 campaign cycle). The implications from this study underscore the importance of popular music within political platforms and will likely impact key music strategy decisions in future presidential campaigns.

– Stan Renard and Courtney Blankenship

Appendix I: Sample titles for genres cited in this study

Hard Rock – “More Than a Feeling” (Boston)

Rock – “Power to the People” (John Lennon)

Pop – “Stronger Together” (Jessica Sanchez)

Soul – “Let’s Stay Together” performed by Al Green

R&B – “Don’t You Worry ‘Bout a Thing” (Stevie Wonder)

Country – “Everyday America” (Sugarland)

Hip-Hop – “Unite the Nation” (Misa/Misa)

Alt Rock – “Even Better Than the Real Thing” (U2 )

Pop Songs on

Political Platforms was published in the Journal of Popular Music

Studies on August 18, 2017. The full article is available through open

access here. Courtney and Stan

are excited to be joining the impressive list of contributors at Trax on The

Trail as they gear up towards the 2020 elections. You may reach them by email

at cc-blankenship@wiu.edu and stan.renard@utsa.edu.

[i] Figure 2 is labeled as Figure 15 in the full article.

[ii] Figure 1 is labeled as Figure 13 in the full article.